The Bus Project

Why aren’t children from Hartcliffe ‘on the buses’? Prompted by the experiences of children in Hareclive, this project uses arts-led methods to explore this important question, understanding the effects of “bus immobility” on the children of Room 13. It provides evidence to assess and challenge bus and transport policy in Bristol and beyond.

What did the project involve?

In October 2017, Mia, then aged 11, told the audience at a Festival of the Future City about buses in her home city of Bristol in England:

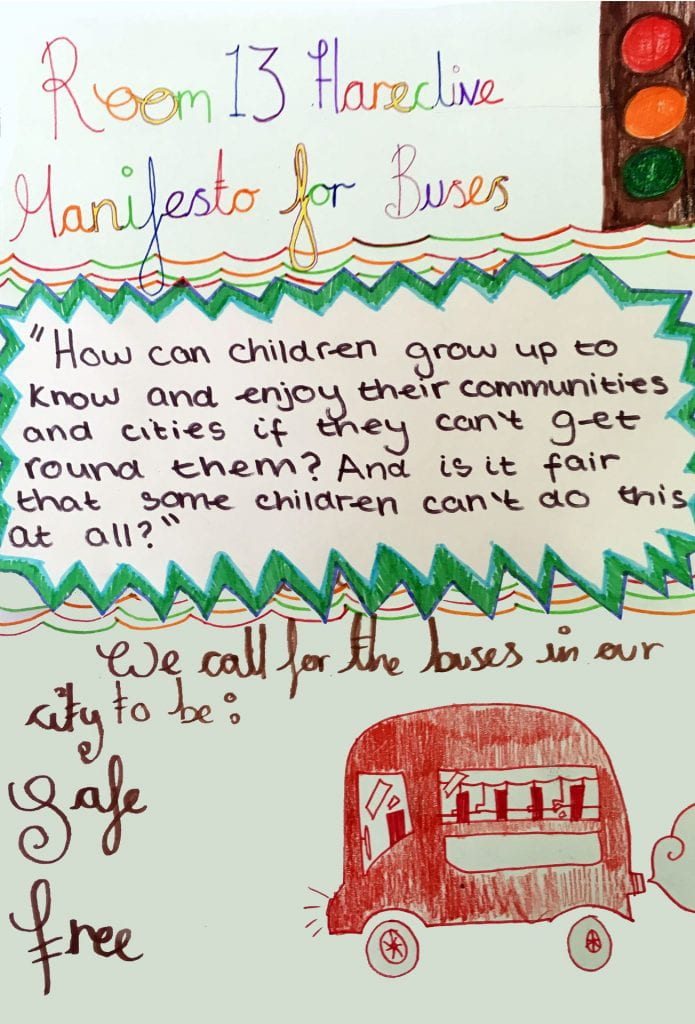

“My family don’t own a car and the bus fares are so expensive. Lots of people can’t get into Bristol to experience everything in the city centre. Some children have never been into Bristol, yet they only live a few miles away. So, I want to ask you: how can children grow up and enjoy their cities if they can’t get around them? And is it fair that some children can’t do this at all?”

Mia highlighted a problem that is not new but is nevertheless shocking. There are children living four miles from the city centre, who have never visited it. While bus ridership in Bristol was rising, children living in Hartcliffe and Withywood, one of the least affluent wards in the country, where over 40% of households have no access to a car or van, told us that despite living close to one of the most reliable bus routes in the city, they cannot reach their city centre because they cannot afford the fare.

Taking up Mia’s challenge, The Bus Project (2018-20) was formed as a collaborative project between academics and Room 13 Hareclive: an independent artists’ studio run by a creative collective of children and adult artist-educators, based in the grounds of Hareclive E-Act Primary. The project could not make reliable causal attributions demonstrating with any certainty whether, or to what extent, economic deprivation causes transport poverty or immobility. Nonetheless, the voices from Room 13 children, parents and carers are loud and clear: buses cost too much, they are often unreliable and unfamiliar to children. Children’s mobility is limited.

Our research in The Bus Project and nearly twenty years of Room 13 experience in Hartcliffe has found that poorer children and young people cannot afford to use public transport and have no choice over whether or not to travel. Many children and young people rarely leave the streets around their home. Artist educators at Room 13 report that: “Every year we encounter children who have never been into Bristol centre, despite living only a few miles out”.

Our research in The Bus Project and nearly twenty years of Room 13 experience in Hartcliffe has found that poorer children and young people cannot afford to use public transport and have no choice over whether or not to travel. Many children and young people rarely leave the streets around their home. Artist educators at Room 13 report that: “Every year we encounter children who have never been into Bristol centre, despite living only a few miles out”.

This lack of access to public transport impacts children’s lives hugely. Children facing economic disadvantage, whose families do not have access to a car, have very little access to active leisure, arts, culture or learning if they cannot afford public transport. The social effects of the Covid pandemic have often increased the impact of the virus on children’s lives, exacerbating disadvantage, poverty and isolation, decreasing life chances. As one parent told us, even before the pandemic: “If I take my children to the dentist, it’s 4 stops away but I have to pay £1 each there and back again with the £4 I have to pay for myself – that’s £8, which is a week of electricity for us at home”. If “levelling up” is a serious ambition, we urgently need to address these transport inequalities.

The Bus Project found that children cannot afford to travel on buses because of a series of political decisions: (1) to fix bus prices at market prices; (2) to grant free concessions to elderly and disabled passengers, regardless of income, whilst giving no national concession to even the poorest youngsters; and (3) to prioritise local supplementary funding for routes and extending national concessions to 9am, rather than providing funding for children on young people.

The Bus Project’s findings are set out in a report Not on the Buses. This includes children’s evidence of the effects of unaffordable buses including (i) constraints on leisure, active hobbies and socialisation; (ii) a lack of independent mobility; and (iii) belonging to their city and wider community. The report also sets out the regulatory framework for decision-making around buses and explains how we could fund the estimated £59.50 a year it would cost to fund children’s free buses – either for all children or for those facing the most economic deprivation.

The Bus Project report suggested that at a local/regional scale, free bus fares for children could be funded by (1) (re)allocating discretionary funds from supported bus services to include categories of user (as permitted under the Transport Act 1985); (2) finding other sources of funding, particularly but not limited to young people aged 16-18 for educational or economic development purposes; or (3) using the proceeds of either a road pricing or workplace levy scheme. The report did not recommend a single funding source for reform, calling instead for an investigation of possible funding streams.

The result of all this is that children’s lives and life chances are poorer. In London, children have since 2005 had free bus travel, however, the funding package imposed in light of the 2020 pandemic, have included a requirement to reintroduce half fares for children (probably, now, in 2021). One of the reasons used to justify the increase in London fares is that children elsewhere in England do not have free bus travel. Our research lets us investigate the lived experience of this reality, challenging the Secretary of State’s justification for levelling down rather than levelling up.

The project then received further funding from Brigstow to conduct follow-up interviews with some existing research participants (particularly at WECA, BCC & bus companies) to see how the pandemic has impacted on bus provision, for all including children. They also conducted additional interviews in Hartcliffe (including with Room 13) to understand the impact of the pandemic restrictions on the children’s mobility. And sought to identify people and sources of data on bus (im)mobility & secondary/post-16 education, in preparation to a grant application to the AHRC.

Who are the team and what do they bring?

- Antonia Layard: (Law, University of Bristol) will undertake desk based research on bus regulation and conducted interviews with representatives from FirstBus, Bristol City Council and others involved with transport governance.

- Room 13 Hareclive is an independent artists’ studio based in the playground of Hareclive (E-Act Academy) Primary in Hartcliffe, south Bristol, and run by children and adults working together since 2003. Artists Shani Ali and Paul Bradley are co-founders of the studio and the artist educators who work with children in the space day to day. Room 13 is a recognised centre of expertise around children, creativity, collaboration and voice and regularly works on co-produced projects with other organisations where children’s voice is important. Room 13 facilitated and delivered all creative engagement and production with the children producing a short film, as well as the data collection with children in the school. Room 13 is also a founding partner of the Bristol Child Friendly City initiative

- Ingrid Skeels as well as being part of the Room 13 collective, Ingrid is an independent strategic development worker, writer and social change campaigner in the field of childhood focussing on education and play (she is also co-director at Playing Out CIC, another founding partner of Bristol CFC). Ingrid co-ordinated the project between Room 13/the school and Antonia Layard and delivered wider child friendly city elements to the project, ensuring that children’s voices were heard via diverse forums and platforms.

- Finlay McNab runs Streets Re-imagined. He is an urbanist specialising in collaborative design, public realm and liveability and experienced community researcher.

- Phil Jones (Geography, University of Birmingham) is an expert on city geographies, including arts-led research methodologies and sustainable transport. He will advise on the methodology to collect data from the Year 6 children as well as interviewing strategies.

What were the results?

- A film: Now’s the Time,

- A Report: Not on the Buses,

- Two submissions to House of Commons Select Committee on public transport (2018 and 2020),

- A manifesto for buses.

The campaign gained city wide media attention:

- Bristol Post (June 2019) Youngsters launch campaign to get free bus travel for children in Bristol

- Bristol 24/7 (Oct 2019): Meet the Hartcliffe Changemakers

- The Bristol Cable (September 2019) Children are being deprived of feeling part of their city.

Children from the studio had the opportunity to visit city hall and speak with Councillor Helen Godwin about their campaign and research results. This conversation was also broadcast on BBC Points West and the children were interviewed. Room 13 also submitted a statement to the Bristol City Council Full Council meeting in July 2019, and were commended on their work by the Lord Mayor of Bristol.

As a result of their campaign, the Mayor of Bristol has brought forward the aim of free bus travel for children and young people in the One City Plan. And Labour MP Karin Smyth has stated free bus travel for young people as one of her priorities for Bristol South.

The project culminated in the law research paper and policy briefing entitled ‘Not on the Buses‘ by Layard et al. A summary of this briefing can be read here under the title ‘Not on the Buses: reduce inequality by subsidising bus travel for Bristolian children‘. Moreover, Anyonia Layard and Room 13 published an open access article in the Journal of Law and Society entitled: ‘Vehicles for justice: buses and advancement‘ which was shortlisted for the Socio-Legal Studies Association Best Article Prize.

The film – proposed, devised, and made by children from Room13 Hareclive entitled ‘Now’s the Time’ – can be viewed below:

Project Social Media