The Unsettled Planet: Quantifying and Communicating the Instability of Terra Firma

How might bringing together artists, scientists and researchers in the humanities with shared interests, generate insights into a shared language for research and creative practice? How can we better communicate risk levels associated with ground movement?

The study of seismology reveals the activity of the Earth on all length and time scales: the ground outside our front doors, as well as the ground beneath the farthest reaches of the globe, but also the ground throughout Earth’s geologic history. Normally, these ground motions are only perceived using sensitive instruments (seismometers are planetary stethoscopes), but occasionally we hear, and feel, their full roar. As we rely on keeping our feet firmly on the ground, both metaphorically and physically, the impact of such ground shaking events can be unsettling and even catastrophic. How one lives with such uncertainty varies with context, personal experience and public understanding.

What did the project involve?

This multi-disciplinary team aimed to initiate conversations around living with such uncertainty, questioning ideas of a stable planet. Collaborating with those who study literature, the environment, art, history and engineering, they explored questions about uncertainties and existential threat. This included questions around mortality, the distinctions that separate cultural from natural, the nature of knowledge and the rationality of belief.

The project came in two phases.

Phase one – Art and science installation: ‘A day in the life of a bell – a study in sound and vibrations’

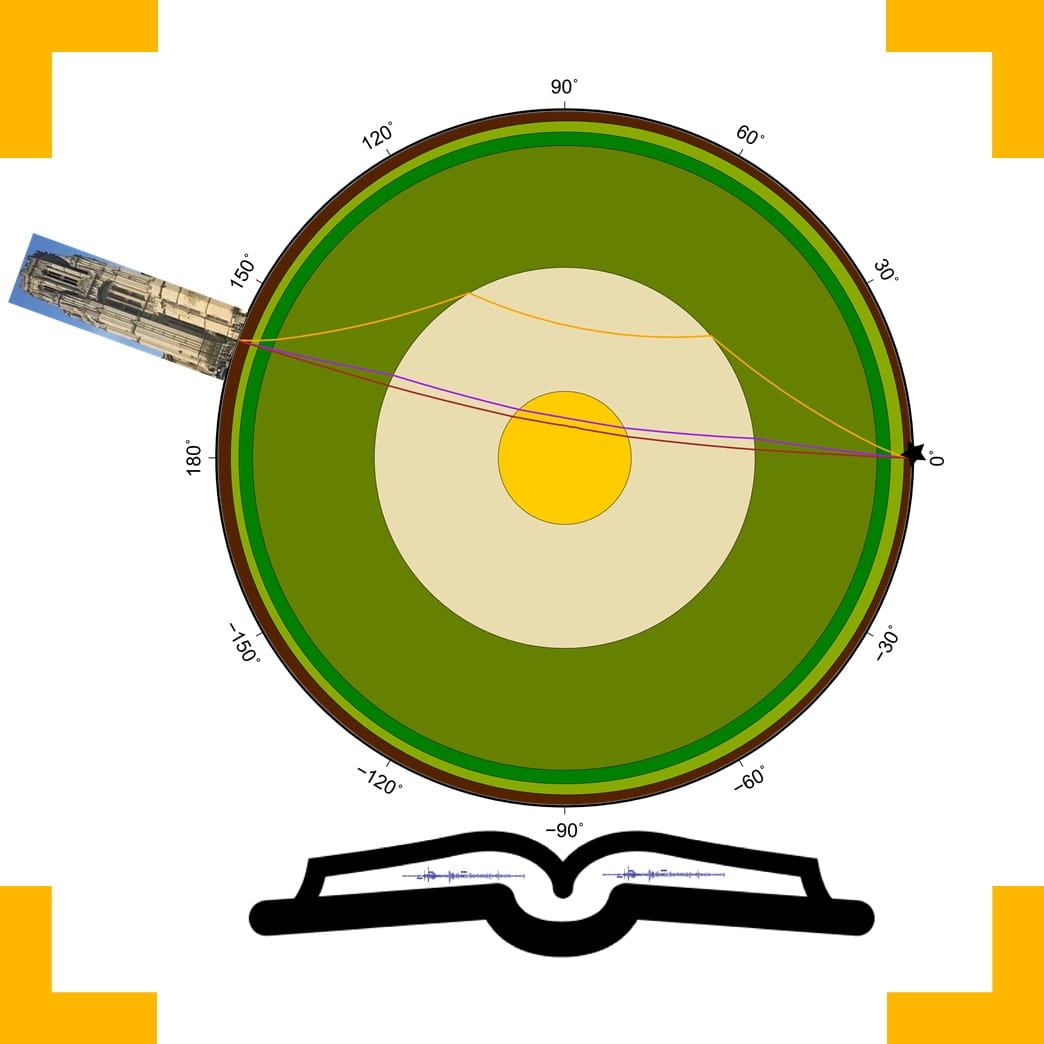

Bells have a rich history in announcing natural hazards, such as earthquakes. The team instrumented the Great George bell in the Wills Memorial Building with a seismometer, amplifier, camera, and data logger. The bell recorded cultural noise in Bristol, but also distant earthquakes from as far away as Japan and other seismically active regions, but with regular punctuation from its own bell clapper.

The data stream was communicated through both visual and audio media and social media. Existing public tours of the tower provided an opportunity to engage with public (potentially from countries with different levels of familiarity with discernible seismic activity and experiences of unstable ground). Climbing a tower itself makes one conscious of one’s relationship to the ground.

Phase two – Multidisciplinary workshops on earthquakes and ground vibrations

This workshop explored the role of earthquakes in human history, literature and art, and their environmental impact. Issues of length scales, time scales, intensity of ground shaking, and impact on the built environment, were addressed. A separate team workshop was held in the Special Collections of the University library, which allowed the project team to look together at printed material on earthquakes ranging from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, drawn mainly from the Eyles collection.

Who are the team and what do they bring?

- Michael Kendall (Earth Sciences, University of Bristol) is a seismologist who studies the Earth’s deep interior using earthquakes. He has deployed seismic instruments in regions as diverse as the Canadian Arctic and the Afar regions of Ethiopia and Eritrea. During the project, he was part of the Earth Sciences department at the University of Bristol, but he has since moved to the University of Oxford.

- Shirley Pegna (Oxford Brookes University) is a musician and sound artist interested in sound as a material. For her PhD, the Transit of Sound and the Perception of Sonic Phenomena, her works created for the study enable audiences to perceive the planet’s physical properties as articulated through sound.

- Tamsin Badcoe (English, University of Bristol) has research interests in how early modern literature responds to the challenges of occupying a terraqueous world, with a particular focus on the author Edmund Spenser (who reacted in epistolary form to the 1580 Dover Straits earthquake).

- Lucy Donkin (History/History of Art, University of Bristol) works on medieval and early modern attitudes to the ground, including dynamic encounters between ground and body, the visualisation of subterranean space, and the roles of soil and sound in the portability of place. Her research also explores geological and historical antiquities in Italy, affected by seismic activity.

- Ophelia George (Earth Sciences, University of Bristol) was responsible for data analysis, as well as handling all of the lab and tech support. She was also instrumental in writing the final article that came out of the project. She has a particular interest in volcano monitoring and eruption response.

What were the results?

Professor Kendall blogged about the experience here, while Dr Pegna shared her experience, photographs and data here. She worked on additional performances directly related to the project, which is detailed further on her website. This included an installation and series of improvised performances of “Earth Din” at Bristol New Music Festival. These pieces stemmed from recordings of earth activity picked up From the University of Bristol, Wills memorial building via a seismometer. These sounds originated from Indonesia, Greece, and Fiji. Shirley Pegna was joined by Welsh violinist Angharad Davies and improvisor-composer Dominic Lash in an improvised sound, bass violin and cello performance that interacted with the field recordings.

After all the momentous activity involved in this project, the team were able to co-write an article for Geoscience Communication journal entitled ‘Good Vibrations: Living with the Motions of our Unsettled Planet’. You can read the article here. Dr. Badcoe also wrote a literature-focused article, published in Spenser Studies in 2022.