Microbes, Microplastics and Man Micro-entanglements and the biological complexes of human and more-than-human collisions

The diatom as a micro-space/organism will be at the heart of the project as a thinking-making trigger and to communicate beyond the project. Can we imagine a time when we take responsibility for the health of our water systems? What might an arts practice look like as a result of this speculative dialogue?

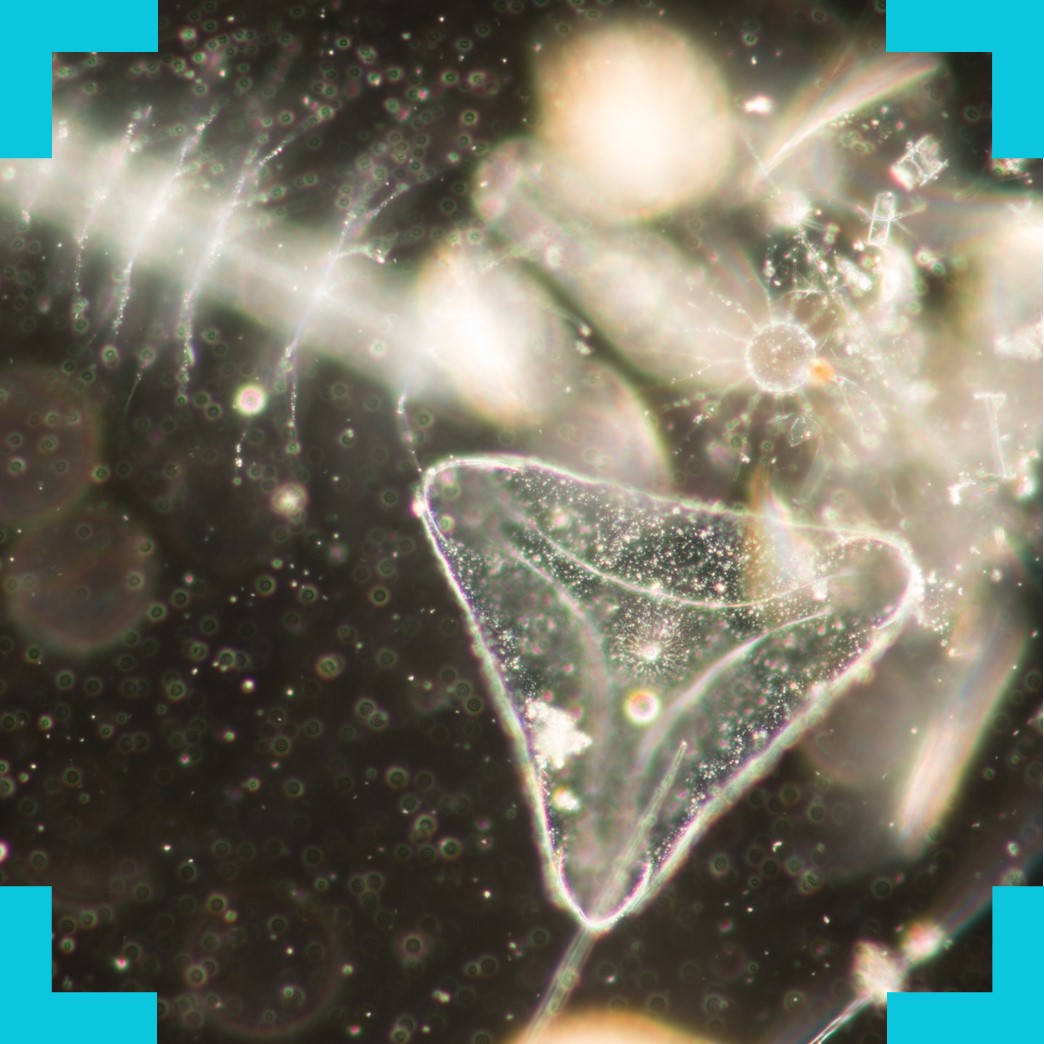

Microbes, Microplastics and Man takes as its starting point the role of diatomic life in the carbon cycle. Diatoms are ubiquitous and multi-species, single-celled, siliceous micro-organisms living in oceans, rivers, mudflats… everywhere. They are a major part of the ecological food chain, essential for nurturing the health of the planet and therefore human life. Through photosynthesis, diatoms are responsible for the conversion of carbon dioxide into organic carbon thereby releasing significant quantities of oxygen into the atmosphere. When oceanic diatoms die, they sink to the bottom of the ocean and through geological processes of fossilisation, they form the vast oil lakes that are now increasingly subject to the demands of the ever-expanding human thirst for oil. Discarded plastics break down into microplastics which can be colonised by bacteria and diatoms, thereby transporting cells across the oceans on new life-rafts. In turn, some microplastics can transport dangerous microbes, potentially harming diatoms.

Complex interactions therefore exist between plastics and their associated pollutants and cells, which may impact consumers. It’s a complex cycle of relationships in which human activity plays a crucial, often destructive part.

On a local micro-scale, the rivers and Estuaries surrounding Bristol are teeming with diatomic life yet these sites are also strewn with human produced detritus including micro-plastics. As a result of pandemic and contagion, we are increasingly turning to our waterways for relaxation and mental sustenance; for alternative forms of habitation. Amidst booms in recreational fishing, wild swimming and even calls for clean up of the floating harbour as a swimming resource, the health of our waterways is more than ever on the domestic agenda.

What did the project involve?

The research activities were structured around fieldwork, collecting water/mud samples, and microscopic imaging. The project brought together artists, a cultural geographer, and ecologists to consider complex human relationships with water systems, using the diatom as a focus for critical making and exchange. The research activities included:

- Fieldwork, dialogue and critical making sessions.

- Time to identify synergies, develop research ideas & pathways for future project development.

- Exploratory art practice-led research

- Host a boat based sharing event in Bristol Harbour

- Visual work-in-progress from across the team

- Identifying of future stakeholders

Who are the team and what do they bring?

- Joshua Dean (School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol) researches into aquatic biochemistry exploring carbon cycling and greenhouse gas emissions from freshwater ecosystems

- Marian Yallop (School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol and Fellow of the Freshwater Biological Association) is interested in aquatic microbial ecology and investigating the relationship between benthic and planktonic diatoms and the health of our rivers

- Veronica Vickery (artist and independent researcher (Cultural and Historical Geographies Group, University of Exeter)) www.veronicavickery.co.uk has expertise in the micro/intimate human geographies of living on and around our waterways

- Chris Neal (Wolfson Bioimaging Facility, University of Bristol) has expertise in micro-imaging.