All images © The Hatchling.

In this blog I will take you on a behind-the-scenes tour of “becoming dragon”: the multi-discipline and multi-sited collaboration that has brought The Hatchling to life. Thanks to Brigstow funding I have been lucky enough to sit in during R&D workshops and performance rehearsals to witness key innovations and stages in the creative development of this project. This blog will take you on that journey of discovery and becoming, and underline the extraordinary talent, expertise and energy that has gone into the making of this ground-breaking theatrical performance. The blog takes the form of a photographic essay and is organized around a series of “landing sites” that have been key to the development of the project.

Landing Site 1: University of Bristol, May 2017

I am in the middle of dissertation marking when I receive an email from Gail Lambourne manager of the Brigstow Institute, a University of Bristol institute set up to foster experimental inter-disciplinary and co-produced research. At this point in the summer marking schedule any distraction is welcome but a message from Gail is particularly so as she is always promoting interesting events and opportunities. This message exceeds expectations:

“Dear Merle,

We would like to invite you to a short meeting to introduce a project that Brigstow has asked to be involved in. The aim is to gather around 15 academics from UoB whose research might intersect with the project. I’m afraid there are some confidential issues which mean we’re unable to share any more detail with you until the meeting, but we hope the following outline might help:

Brigstow has been approached about an arts project of a phenomenal scale. The creative team includes the puppet director of War Horse, a kite world champion flier and set designer for Bjork. The project has some key research and public engagement opportunities which will reach audiences in their tens of thousands.

So we would like to invite you to meet the creative director of the project to find out more.

Having looked at calendars, we are proposing Wednesday 12th July between 2.30 & 4.00 pm for the meeting. Would you be interested in attending?

I look forward to hearing from you.

Best wishes,

Gail”

A tingle of excitement runs up my spine. An arts project of phenomenal scale the creative team behind which includes the puppet director of War Horse and the set designer for Bjork: sign me up! I immediately reply in the affirmative to Gail and it’s not long before I and several other academic researchers meet Angie Bual, an award-winning producer and the artistic director of Trigger – a Community Interest Company that creates memorable live and digital events that interrupt daily life – to find out more.

Angie begins by telling us a story. One morning a mysterious giant egg appears in the centre of a city. The city’s inhabitants are intrigued and alarmed by its unexpected arrival. Will it hatch? What will hatch? Will it be friendly? When the egg hatches later that morning a baby dragon emerges, unsure of its urban surroundings and the human interest in it. Apprehensively, she begins to take her first steps and sense her surroundings. She is both curious and cautious. A dog bark intrigues. Traffic lights and sirens unsettle. Getting bolder she roams the city streets interacting with the sights and sounds and people and places she encounters along the way. Fatigued after an overwhelming day she finds a good place to build a nest and rest for the night. Although she has settled down for the evening her human co-inhabitants are left with a conundrum: what should they do about their new visitor? Should they welcome her or be wary? The next morning the dragon has doubled in size. This day she is more confident and purposeful when roaming the city. She is seeking something. As the sun is setting, she finds what she has been looking for – a pearl! – then undergoes an incredible metamorphosis and takes flight after it, leaving behind her awestruck human audience.

What an audacious idea. But any reservations there could be about the scale and ambition of this city-wide theatrical spectacular are not entertainable. Everyone who has just witnessed Angie’s pitch knows that she is the woman to make this event a reality. She tells us that the idea was partly inspired by a trip to China, where she learnt about Chinese dragon folklore and their highly crafted and intricate dragon dances. Recognizing that dragon legends and story patterns reoccur not just across China and Asia but also across Europe and the British and Irish Isles, Angie thought that a performance centred around a dragon might be an effective way to connect cultures, traditions, and communities.

Gail then outlines why academics have been invited along to hear about Angie’s project, a project that is not only charting new ground in the world of puppetry making but also offers the opportunity to explore the role co-creative large-scale puppetry can play in engaging urban communities and environments and addressing the themes of belonging and migration, as well as cross-cultural folklore and mythology. Brigstow has small pots of money to help facilitate academic research into and public engagement opportunities around the performance, and Gail invites us to come up with ideas and to apply for funding. Given my previous research into taxidermy, the craft skill of preparing and mounting animal skins to appear ‘lifelike’, I was immediately interested in researching the puppetry craft and performance skills needed to make a mythical creature come to life.

The funding application leads with the question: How do you develop, make and embody a believable yet mythical beast based on various real and imagined creatures that “reads” as one? Titling the project “Becoming Dragon”, I am not just interested in the animal references, real and imagined, that will inform both the making and performance of the dragon but also the multi-faceted creative collaborations needed to enable a human-operated puppet roam a city’s streets and take flight, a world first in the world of puppetry. However, rather than just witness this process from the side lines, I state the project will feed into and create a valuable record of the process of “becoming dragon”.

I submit my application and a few weeks later hear the good news from Gail that the project has received funding from Brigstow and that I can join The Hatchling team for their first R&D workshop.

Landing Site 2: Former British Aerospace Factory, Filton, December 2017

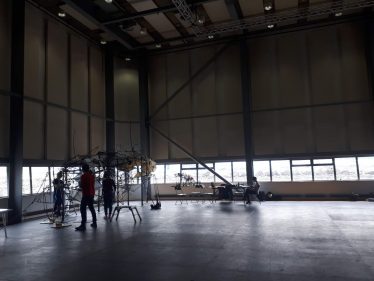

I arrive at the former factory of British Aerospace and immediately get a sense of the scale of the project. The cavernous hanger, where numerous aeroplane prototypes and designs were once built, including Concorde , is now the R&D workshop for the project. Angie gives me a tour of the space and introduces me to the large-scale walking and flying dragon prototypes that are already competing for my attention.

It is fitting that the research and development stage of a project attempting to make a human-operated puppet fly is taking place at this historic centre of aviation innovation. Angie informs that for the flying dragon prototype they have been experimenting with makers at Cameron Balloons. The idea developed so far is that the walking dragon puppet will house an inflatable dragon so that when the time comes for the dragon’s metamorphosis, the walking dragon puppet structure will burst open as the flying dragon inflates and takes to the skies. Conceptually this idea is as beautiful as a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis. Technically it sounds like a demanding design puzzle. Having read about the history of the Filton site before arriving, many of their prototypes failed to reach flight and I marvel at the ingenuity, skill and sheer chutzpah needed to pull this theatrical stunt off. And as if to quell any questioning the flying dragon prototype majestically inflates and is run across the hanger like a soaring kite by members of the creative team.

Angie turns attentions back down to ground level by introducing me to the walking dragon puppet prototype and her designer Carl Robertshaw. Carl is a world champion kite-flyer who has been designing and making kites for over 20 years as well as designing and consulting on fabric structures and installations for performances, events and installations using kites as his main inspiration. If anyone has the know-how to make a sculptural walking form metamorphosize into a flying one, it’s clearly Carl.

He takes me over to the prototype of the adult dragon and reminds me that there will also be a juvenile dragon puppet. Standing next to the adult dragon prototype I get a sense of her awesome size. She could certainly be intimidating to meet walking down a city street. For the moment though, her structure is made from thin flexible plastic tubing and tension ropes, which makes her appear skeletal and delicate. Carl then introduces the scale model of the adult dragon which he built on “mum’s coffee table” and I get a much better understanding of the “look” of the dragon. Carl confides that her body structure has been highly influenced by the body and wings of Pterosaurs, prehistoric flying lizards that were basically “catapults with arms”. Pterosaurs were also the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight so it makes sense that a dragon might have descended from them. Meanwhile her head and face have closer affinities with Chinese dragon-dance puppets. Carl states this is deliberate as it not only makes her appear more sympathetic, but also importantly references the Chinese folklore and performances that initially inspired Angie. The dragon is therefore a chimera of different animal and cultural references.

Carl then introduces me to Russel Beck, a leading theatre and stage prop-maker, who is collaborating with Carl on the puppet build. Today they are workshopping the puppet’s range of movement with the performers. Russel states that what they do not want is “a box on legs” and that the structure needs mobility. Yet at the same time they also do not want the structure to be so mobile that she lacks “bodily integrity”. Carl adds that both they and the performers need a “responsive structure” that tells them “what the body can and can’t do” and that this responsiveness must come as much from the puppet as much as from the performers.

As if on cue the performers appear and assemble around the adult prototype. I am introduced to the leader of the troupe and the project’s director of puppetry, Mervyn Millar. “Merv” is one of the world’s most experienced puppetry directors and was part of the original creative team behind the National Theatre’s ground-breaking production of War Horse. This production was consistently praised for the power of its puppetry, which Merv co-devised and directed. Although the audience could see the that the puppets were human-operated, there was something about the combination of the intricate life-size sculptural-horse puppets and the realistic movements created by their puppeteer-operators that meant the hybrid human-puppet-horses took on lives of their own.

Mervyn has reassembled some of the War Horse puppeteers for this R&D phase and it is now his and the performers’ job to work out how to breathe life into the dragon puppets. However, before that magical alchemy can be achieved Mervyn informs that they have far more prosaic things to work out, like “how the poles work”. Much like a traditional Chinese dragon puppet, the head, shoulders and hips of the prototype adult dragon are lifted and operated by several poles. The poles allow the puppeteers to manipulate these different body-sections and the puppeteers must be able to co-ordinate these movements with the performers who are operating the legs and the tail so that the dragon has a convincing and compelling walk.

Today Merv is particularly interested in learning about the range of movement and weight distribution as “there are various things we don’t yet know about the puppet”. He tells the puppeteers to experiment with movement and range but to always shout “stop” if uncomfortable or it “feels off”. Russel adds they are also concerned to understand “how it moves and how you move with it” and to ensure both the performers and puppets “survive the performance”. The health and safety of performers and the robustness of the puppet are paramount.

The performers take to their places on the prototype puppet body. Three performers are assigned to the poles on the head. Sets of two performers are assigned to the poles on the hips and shoulders, while the four legs and tail are assigned to a performer each. All the pole operators are asked by Merv to lift in unison and the puppet body wobbles upwards. Carl tells me they have not yet worked out what they are doing with the neck and that it is “floating for now”. Although still a little wobblily the dragon body starts to cohere as the performers settle in their positions under her body.

Merv instructs the operators that before they start moving it is important to not think of themselves as “components parts” but as a “whole living, breathing” dragon. To assist in this, he asks them to “think about breath” and he directs the shoulder operators to lead the dragon’s breath. The two operators start to breath heavily in unison and begin to lift their poles up and down with their inhale and exhale. Merv then instructs the other operators to “match this breath and movement”, which they do. At this, the dragon’s body begins to look like it is inhaling and exhaling, becoming animate for the first time.

Having gotten the performers to breath as one, Merv suggests to the head operators that the dragon has “heard something” over in the corner of the hanger and they duly lift and tilt the head, as if she is listening. It is only a small movement, but it gives the dragon an alertness she did not have before. Merv reminds the performers to think about the “three Rs”, which he later tells me are “Reaction, Recognition, Responsiveness”. In this case, the dragon reacts to the sound by moving her head, recognizes that it is coming from over in the corner and so now needs to respond. Merv suggests that the response is that she wants to move closer to the noise to investigate. This means that the puppeteers face the challenge of making her walk.

Attention turns to the performers operating her legs. Merv reminds everyone to “try to keep the breath going” as that rhythm should “help generate and propel the movement”. Merv instructs the performers to “try out the lizard walk” (which I find out later they have been researching by watching youtube videos). Lizards walk by moving diagonally opposite feet simultaneously, the left fore foot with the right hind, and the right fore with the left hind. There is a little hesitancy between the left and right dragon fore legs as neither appears sure which should move first. Once the right decisively goes for it, there is a bit of lag before the left hind legs move forward in response. The left fore leg then springs forward but again there is a delay before the right hind leg responds. As they lumber forward in this pattern of movement the back legs are constantly playing catch-up and at times appear improbably stretched behind the rest of the body. Yet as they pick up speed the delay between the diagonally opposite legs moving forward lessens and the dragon takes on a lolloping if not strictly lizard-like stride.

Once the dragon reaches her destination Merv tells the performers to “Ok stop”. He then asks the performers to let him and Russel know how “she handles and feels” so that they can make any necessary changes and adjustments. The left hind leg operator feeds back that at times the legs felt “too outstretched” and that it was difficult to “keep up and in sync”. Merv responds that it’s important that the operators all communicate with each other and that means “talking to one another” but that they also need to work out how to do this without “losing the dragon”. He also states that it’s ok if “our dragon doesn’t exactly walk like a lizard” and that they need to “work out her walk”. The shoulder pole operators then feedback that it felt like they were being “pulled in in different directions” and that they were “taking a lot of strain” when the hind legs lagged behind the fore legs. In response, Russel suggests that he and Carl might need to restrict the range of movement in the back lags to prevent or at least “reduce this”.

Listening in to this feedback session it is clear that “becoming dragon” is not just a case of perfecting a walk or developing a character, rather, it is an iterative and co-creative process between director/puppeteers and designer/maker and the puppet-prototype.

Landing Site 3: Rusell Beck Studio, London, January 24th 2019

I arrive at Russel Beck Studio excited to find out how the puppet design and build are progressing. The Studio is the UK’s leading workshop for the design and fabrication of props, sculpture and models for theater, exhibitions, and events. The double-height studio space’s walls are lined with the tools and materials of the trade as well as boxes tantalizingly labeled “Felt”, “Rubber”, “GLITTER”, “Zorro” and “Avenue Q”. Russel gives me a brief tour of the space and introduces me to a team of prop-makers at the back of the studio who are busily engaged in making replacement ivy, a weekly job, for a production of Les Misérables. He then takes me back to the front of the workshop where Carl and Merv introduce me to the “new and improved” models of the juvenile and adult dragon puppets that Carl and Russel are in the middle of designing and making.

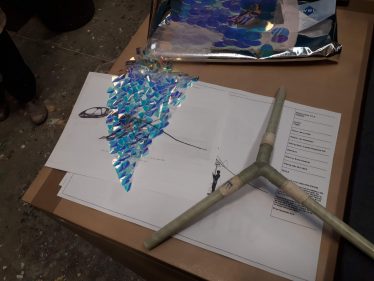

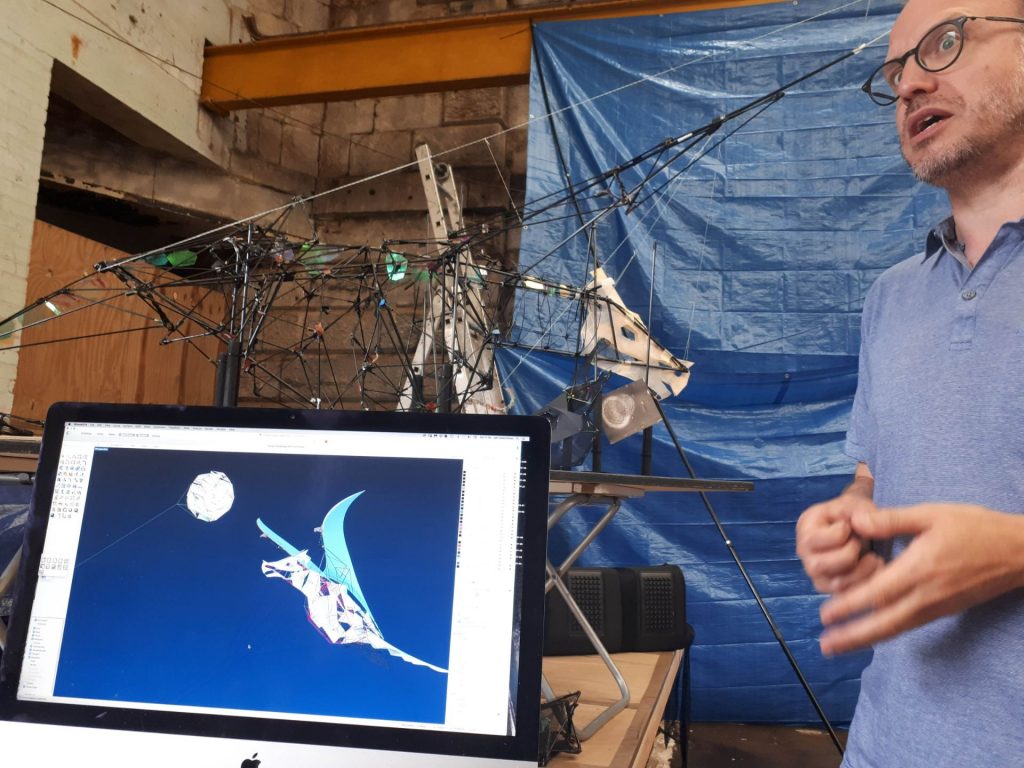

The first thing I notice is that the heads, which are made from tracing paper and card, are much more characterful. Although made up of a series of geometric shapes, the overall sculptural effect is surprisingly friendly and open-faced rather than harsh or hard-edged. Carl informs me they plan to further soften the dragons’ sculptural and skeletal base structures by covering them in layers of translucent stretch fabric. He is hoping that these layers will help to build up a sense of the dragons’ musculature and skin while also suggesting “lightness and flight”. Carl brings out some of the fabric swatches they have been experimenting with, including some swatches of large iridescent sequins that will give the dragons’ a magical shimmer.

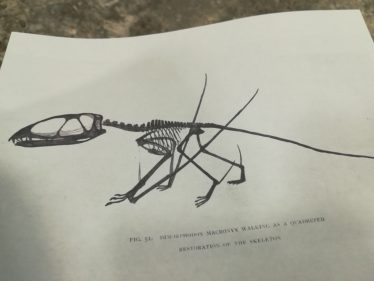

Carl places one of the sequined swatches over an image of a Pterosaur, one of several reference images that are lying next to the models. I read that this image is of “Dimorphodon Macronyx Walking as a Quadruped”. The image is a photocopy from Harry Seely’s popular 1901 book on pterosaurs, the wonderfully titled Dragon’s of the Air. A British paleontologist, Seeley correctly contended that Pterosaurs were warm blooded active flyers as opposed to Richard Owen’s earlier characterization of them as cold-blooded gliders. The question of if and how pterosaurs walked was an open question for paleontologists at this time and Seely posed Dimorphodon Macronyx as both a quadruped and biped in his book. This conundrum was answered in 1957 when William Lee Stokes found pterosaur tracks that were quadrupedal and although his attribution was dismissed at the time, several examples of quadrupedal pterosaur tracks were found in the 1990s that corroborated pterosaurs walked on all four limbs just as posed in Seeley’s image “Dimorphodon Macronyx Walking as a Quadruped”.

Carl relates that Mark Witton, a paleontologist at the University of Portsmouth, introduced him to this rich history of scientific speculation and that it was conversations with Mark that informed his early design ideas for the dragons. For example, it was Mark who told Carl pterosaurs were quadrupedal and that they likely used a vaulting mechanism to obtain flight, a bit like vampire bats. Mark also told Carl that the Smithsonian institution once commissioned an aeronautical engineer to build a half scale remote-control flying model of a pterosaur to appear in its Imax documentary On The Wing (1985). Although the latex rubber and Kevlar Quetzalcoatlus northropi model was filmed flying for the documentary it spectacularly crashed as part of its publicity tour in front of tens of thousands of spectators. Carl, unfazed by this potentially foreboding story, informs me that they are still trying to work out how the dragon’s metamorphosis is going to work, so that the inflatable dragon emerges and can take off without a hitch in front of their crowd of spectators.

Angie, who has joined us, explains that they have finally secured a city and date for the performance – Plymouth in August 2020 – and she is hoping that the dragon will take off after the pearl from Plymouth’s Hoe promenade, with its spectacular scenic views out to sea. She and her production team are currently exploring how they might turn the dragon’s metamorphosis into a performance event in and of itself by commissioning a composer to set the transition to music. Merv adds that the musical interlude, as well as being an important performance element, will also be important practically, as it will give the puppeteers time to transition the adult dragon from its walking form to its flying form. Yet with so many unknowns still to work out I am amazed by the team’s calm confidence and as if to quell any doubts, Carl excitedly shows me a part of the puppet build they have recently resolved.

Carl relays that the joints needed to hold the skeletal structure together had previously been giving him and Russel a bit of a headache as they were not strong enough to endure the wear and tear of performance. However, after various tests they innovated a triple-joint bonded and toughened with a fiberglass wrap. To prove its strength Carl places the prototype joint on the studio floor and stands on it, whereupon it does not even bend. Impressed, I suddenly think the prototype also nicely reflects the strength of The Hatchling’s three-pronged creative team in: 1. Angie and her production team, 2. Carl, Russel and their making team and 3. Mervyn and his puppeteers. The combination of their respective skills, expertise and experience creates the perfect trifecta.

Landing Site 4: Theatre Royal’s TR2, Plymouth April 23-25th 2019

I have come to the Theatre Royal’s TR2 to watch the puppet rehearsals and gain an appreciation of Merv and the puppeteer’s approach to bringing the dragon to life. The figure of the puppeteer is fascinating yet understudied in theatre and performance studies (though see Astles 2009, 2010). This is because the puppeteer as a performer has traditionally been required to disappear, which is why they dress in black. The puppetry in War Horse was ground-breaking as they did not attempt to hide the puppeteers from the audience, rather, the puppeteers formed part of a performative alliance with the life-sized horse puppets so that they became an essential and unquestioned part of the horse performance. Although dressed in the same period costume as the actors, the puppeteers did not appear as all-powerful actors imposing their will on an inanimate object, rather the performance came from the relationship developed between the sculptural horse body and the human puppeteer bodies – it was through this interplay that a believable “horse” emerged.

Merv confides that part of the reason this interplay worked so well for War Horse was because both the designer and the puppeteers studied equine movement and behaviour. The designer was therefore able to build puppets that could move like horses while the puppeteer bodies were trained so that they could express and perform “horseness”, as Merv puts it, when operating the puppets. Given a dragon is a mythical animal I ask Merv if this makes the task of creating the dragon performance easier. Merv agrees that they are “less constrained” in some ways as they do not have to be so concerned with creating “accurate movements and behaviours”, however, they still need to base their dragon on realistic animal movements and behaviours so that an audience can invest in the dragon as a “believable beast”. This is also why Carl has gone to such pains to trace a probable evolutionary history for dragons and why pterosaur anatomy became the building blocks for his puppet design.

With the dragon design DNA decided upon it is now the task of Merv and the performers to create an impression of believable animality or “dragon-ness” when operating the puppets. As well as watching animated recreations of pterosaurs moving and flying, Merv and the cast have also been researching the movements and behaviours of lizards, Komodo dragons, vampire bats and even gorillas in a bid to build up a plausible physical and behavioural vocabulary for the dragons. Yet for the puppeteers it is one thing to attempt to embody these movements individually using their own bodies (and following the example of specialist animal movement coaches on youtube), it is quite another task to work as an ensemble and transmit this mélange of movements and behaviours into a puppet so that it reads as one creature.

However, before they reach this level of performance, Merv explains he first needs to help the puppeteers to develop a sense of themselves not as singular performers but as part of a collaborative “performance ecology” between “living and non-living bodies”. Merv tells me that he developed a repertoire of exercises to help facilitate this transition during his time training the actor/puppeteers for international productions of War Horse (Millar 2007). This morning he is introducing the dragon performers to some of his “stick exercises” (Millar 2018). Although the assembled cast still includes a couple of trained War Horse performers, the majority have no prior puppetry experience. This lack of experience does not seem to faze Merv as they bring “new info and skills to the table”, and perhaps more importantly, do not need to “unlearn” anything.

For the warm-up exercise Merv gives each of the performers a stick and groups them in pairs. He instructs them that the aim is to keep both sticks off the ground by “sharing responsibility for them”. Before they begin the pair need to decide who will be the “leader and responder”. In their pairs the performers pick up their sticks and hold them between each other balancing them on their palms. Merv instructs them to “find their breath”. Once the pairs are breathing as one, Merv gets them moving by offering the prompt “explore your range of high and low”. The partnerships start to tentatively explore the physical limits they can push their new body-stick configurations to. On a couple of occasions, the partnerships overreach and the sticks come clattering to the ground, but Merv reassures them that “you might drop the polls, but it doesn’t matter”. On picking up their sticks Merv reminds them to “enjoy re-establishment of connection and mutual pressure” and “don’t forget breath”.

Just as it seems the partnerships are in tune with one another, Merv instructs the group to change partners and “establish connection and breath with” within their new partnerships. He tells me as an aside that switching partners is important as none of the performers will have a designated place on the puppet dragons, rather, they will rotate places. Merv directs the new partnerships to “hear each other through the object” and to “respond” by “speeding up or slowing down” the movement. He also reminds the partnerships to be aware of their “body-space” and that of the other partnerships, as some of them look like they are in danger of crashing into each other. Next, he prompts the partnerships to explore “angles and crossings” which necessarily leads to more clattering. After several such instances Merv senses a natural pause and asks the group “how was that?”. One of the performers feedbacks that at first it was difficult to “place trust” in the other person’s movement, but that when they closed their eyes it helped them to “to just focus on and respond to the feeling”. Another performer also closed their eyes to “focus on feeling”, but that this made them “less aware of spatial constraints”, including the other partnerships.

If the “sharing sticks” game was about developing trust and reciprocity, Merv’s tells me the next stick exercise is about developing “sympathetic performances”. The group remain in pairs and with a stick each, however, now the “game”, as Merv puts it, is to mirror each other’s movement with the stick. He directs that it does not matter if they are “not exactly mirroring” each other’s movements, rather, the aim is to mirror their “energy”. However, before this mirroring can begin Merv instructs the “leader” of the pair to focus on their stick, to feel its “weight” and give it “breath”. Although there is scant scholarship on the training of puppeteers for contemporary live theatre, Cariad Astles (2009: 54, 59) maintains that for the purposes of performance the puppeteer needs to be trained in a bodily sensibility that can “generate and transmit huge amounts of energy towards the inanimate figure, material or thing”, while also being encouraged to develop “an awareness of the energy held in the thing, respecting the qualities of the [puppet] itself”.

By prompting the performers to feel the weight of their stick, Merv is clearly encouraging the performers to recognize the potential energy held in it. Moreover, by asking them to give it “breath” he is also directing them to transfer the energy of their own breath and movement into the stick. For Astles (2010: 32), the importance of breath in puppetry training cannot be overstated as:

“From the breath comes the movement: the breath and movement partnership create phrases which map the score of the performance. Training the puppeteer is thus to train a bodily awareness of the breath as impulse to the movement, which in turn suggests life.”

Merv is clearly attempting to encourage this type of bodily awareness in the dragon puppeteers, and it is working: when the leaders begin to focus and transfer their breath movement into their sticks these simple objects become animate.

Once the leaders have established a breath and movement partnership with their own sticks, Merv instructs the followers to mirror the leader’s movement. This he tells me is to encourage “complimentary and sympathy” between the puppeteers, which will be hugely important when they come to operate the dragon puppet together. Watching the pairs, it is apparent some of the followers are hyper-focused on keeping in time and step with the leaders’ movements, whereas others seem more attuned to mirroring the overall dynamism of the performance. The latter of these approaches appears the more sympathetic, as they more successfully reproduce the energy of the leader’s performance. To encourage the followers in this latter approach, Merv directs them to “pick up on mood” and to “not to worry” if they fall behind or do not match their partner’s movements exactly. Merv reminds them that the aim is to explore “complementarity” and prompts the followers to match the “quality” of the movement rather than the movement itself. This direction has the desired effect as those that had been struggling to exactly match the movements of their partner now relax and become more attuned to the breath and mood of the leader’s movements. As Merv moves from partnership to partnership he reminds them to “stay sensitive and sympathetic” and to “remember it all comes from breath”.

Reading Astles’ (2009, 2010) work on my train journey home and her argument that breath and sympathy are the central sensibilities one needs to train a puppeteer in so that they can give the impression of life in otherwise inanimate objects, I realize that I have just witnessed a masterclass in puppetry training.

Landing Site 5: Royal William Yard, Plymouth August 14/15th 2019.

Natalie Adams, a senior producer of The Hatchling and co-director of Trigger, reminds me over email rehearsals have moved site to Royal William Yard Plymouth, as the site has indoor and outdoor rehearsal space. When I arrive at the yard, I find out that the term “indoor” to describe the dilapidated warehouse space they have set up camp in is perhaps a little generous, as it is almost completely open to the elements. But as Merv breezily annouces when he comes to greet me: “the performance is happening outdoors, so we need to get used to it!”.

Merv takes me over to Carl who has some “exciting news” to depart. Carl informs that there has been a major creative development in the puppet build: the walking adult puppet is now also a walking kite that will take flight. He recounts that the transition of the walking dragon puppet into the inflatable flying dragon had been causing problems both in terms of the build – storing the inflatable in the frame of the puppet was proving problematic – and in terms of performance – the team were worried they might lose the audience’s emotional investment in the dragon when it metamorphosized into its different inflatable form. Carl’s elegant solution means that the adult dragon puppet-form will both walk and take flight. The puppeteers still need to transition her from “walking mode to flying mode” so the metamorphosis performance remains in place, but the kite innovation means that the transition will be more practical in terms of build and more plausible in terms of transition/performance. It also strikes me that it beautifully reflects Carl’s expertise in kite-making and flying.

Carl and Merv want to get the puppeteers onto the adult puppet build this morning so they can see “how she is handling”. She is so large the performers need to walk her out of the warehouse so they can get a better view. As the puppeteers take their positions on the poles and legs, I run ahead with Carl and Merv so that I can see her emerging from the shadows of the warehouse and into the light of day. Merv comments that “something magic happens when you take a puppet outside and it interacts with the elements” and he is right, when her head emerges around corner of the warehouse door and appears to sniff the air, she takes my breath away. As she walks towards us in the carpark, I note the puppeteers are roughly following the pattern of a lizard walk but that because now she more clearly appears to be walking on winged forelimbs, she takes on the appearance of a stalking vampire bat. She is quite intimidating.

Merv sensing my awe relates “a puppet in an open space creates its own theatre, it changes time like dance”. And time does seem to stand still while I take in the uncommon site of a dragon strutting around a carpark. Merv then turns to the dragon and offers the prompt “she becomes transfixed by that red car”. In response the head pole operators lift and crane her neck and head towards the car in the far corner of the carpark, so that she focuses her attention on the car. It is just a small series of movements but as they do so the shoulder operators speed up the rhythm of her breathing, so that she takes on an added mood of alertness. The speeded up breathing also has a ripple effect though the body and the tail operator begins to whip the tail back and forth in response completing the “three R’s”. Then one of the shoulder operators offers “she wants a closer look”, and she begins to strut towards the car. Carl, who is standing next to me, states “it’s good to get a look at how she moves” and says to Merv “the spine’s still too flexible”. Merv responds that “perhaps we can give the illusion of a strong spine”, to which he then directs the pelvis pole operators: “try to stay in alinement with the shoulders”. The pelvis pole operators try to dampen the spine’s flex but as she walks towards the car the dragon still has a distinct S-bend walk, not unlike a Komodo dragon.

When the dragon is nearing the car, Merv, sensing a tentativeness from the performers, prompts “she’s wants to communicate dominance, so think about the Gorilla stance”. In response the forelimb operators adopt a wider stance whilst the shoulder and head operators lift up their poles so that she grows in stature. Then Merv instructs “OK let’s try out a roar”. In response her breathing, led by the shoulder operators, becomes heavier and louder and as her body expands and contracts to this rhythm the head and shoulder operators begin to make a low guttural sound. Merv asks the performers to “think about where the emotions located… perhaps a growl comes from the back?”. The pelvis pole operators offer some growling sounds, and this helps to build the noise, but with the wind picking up and seagulls raucously calling overhead Merv encourages them to “be loud” and reminds them that it is “better to do it too big so you know where wrong is”. However, although they do build the noise the overall sound effect comes across as more of a snarling grumble than a full-on roar.

As the sound peters out Merv takes this as a cue for rest and reflection so asks the performers: “Ok so what have we learnt? Let’s talk movement first”. One of the pelvis pole operators feeds back that they are still having to dampen a lot of movement and as a result are taking “a lot of strain”. Carl acknowledges the spine is still too flexible and that he and Russel will investigate how they might better “stabilize it”. Then one of the hind leg operators notes that the leg “still feels a bit leaden”. In response Carl states that “we can add more bungies to give her more of a spring in her step”. He then notes this request in his notepad whilst telling me that “we actually need more connective tissue (the bungie cords) all over the carbon-fiber structure to help the limbs spring back and to cushion the movement”. He also informs me that every requested change to the build also gets logged in the computer model and that the build is a “constant process of tweaking” in response to the feedback from the performers.

Next another performer notes that even though the structure lacks a bit of spring “the impulse is always to move forward”. Merv responds that they need to “fight this impulse” and work in more “moments of stillness”. He continues that these “landing sites” will not only give the audience a chance to catch up and “feel the emotion” it will also give the performers a chance to rest and anticipate the next move. He also reminds them that “the dragon cannot spend the whole day walking around Plymouth as she and you (the performers) will need to conserve energy”. Merv also tells the group that they are “still being too polite”, which makes for a “quiet and tentative dragon” and that after lunch they will work on making the dragon “come alive vocally”.

Over lunch Merv imparts that for War Horse, it was never intended that the puppets would vocalize, but that when they started playing about with noises in rehearsals, they recognized that they helped to communicate emotion and character and thus were incorporated in the onstage performance. This meant that as well as researching equine movement the puppeteers, who were mic’ed for the duration of the performance, were tasked with researching and practicing equine vocalizations and communications, including “snorting, nickering, whinnying and squealing”. Merv then imparts that the question of “if and how” the dragon should vocalize is still a “live question” and that he will engage the performers in a “sound bath” after lunch to explore. On my asking what a sound bath is he informs that traditionally a sound bath is a healing therapy that uses sound, usually made by a “singing bowl or tuning fork”, to induce a meditative state but that he uses it as a vocal warm-up exercise.

After lunch, when he and the performers have reconvened in the warehouse, I witness how Merv has adapted this ancient practice. First, he gets the cast to stand facing-inwards in a close-knit circle so that their arms and bodies are touching the person either side of them. He then asks them to close their eyes and instructs them to slowly increase the sound of their breath so that everyone in the circle can tune in to the same breath. Once they are breathing as one, Merv prompts them to explore making sounds on the in and out breath and to “keep listening and responding” to each other. The noises made on the out-breath sound like descending yawns whereas those on the in-breath sound like shrill yowls. Merv then tells the circle he wants them to take responsibility for “making offers” and to let the sounds “volley” around the circle. Someone begins to groan and then several other groans and moans reverberate around the circle in response. Then someone starts clacking their mouth and the circle slowly starts to transition from moaning and groaning to clicking and clacking to meowing and trilling noises and the circle starts to caterwaul. Merv reminds them to switch their “brains off” and “become more feeling-led”. Over time the ping-ponging of noises lessens, and the circle settles on snoring on the in breath and growling on the out. The sound is low and guttural to begin with but as the volume increases and layers of bellowing and snarling sounds are added, the deep rumble builds to the crescendo of an impressive roar.

The dragon has awoken.

Landing Site 6: Home Office, Bristol August 28th and September 9th 2020

I get an email from Natalie with “exciting news!” – they plan to test fly the dragon the following week and would I “like to join?”. It is indeed exciting news to receive after The Hatchling event was cancelled and the dragon was grounded due to the emergence and world-wide spread of Covid-19. And although I cannot join them for the test flight it is heartening to learn that The Hatchling is still in development as I have read with concern that those working in the cultural and creative sectors have contained the greatest share of jobs at risk during the pandemic, as many jobs in these sectors have not benefitted from the policies and schemes put in place to support firms and workers. There has even been talk of encouraging creatives freelancers to retrain in “viable” jobs. Yet instead of dismissing the arts, the pandemic has shown that now is the time to cherish and support them as in such times of crisis they not only generate positivity, appreciation, and hope, but can also help us to face up to injustices and process global events.

A few days later I get the following WhatsApp message and image from Angie:

“she flies!”

On seeing the dragon soar, I think about how this feat of design, engineering and imagination has been accomplished by the expertise, hard work and passion of Angie and The Hatchling’s amazing creative team and that when the dragon does finally take off from The Hoe, she will lift the spirits of all who watch her.