Meeting Points

How do connections between the people and place where one lives affect and effect a sense of living well? Can collaboration and creative intervention positively impact upon the wellbeing of a street?

There is a common assumption that neighbourliness and street–level interaction and connections have diminished, as contemporary society has become more mobile and individualised, and as residential streets grow increasingly diverse; particularly in relation to class and ethnicity. A consequent assumption follows, that this situation negatively impacts on people’s lives.

What did the project involve?

Focusing on two Bristol streets in the diverse neighbourhoods of Easton and Southville, and utilising the innovative creative interventions of Mobilehome Gallery and Human Canvas, the project had two key aims:

- To expand our understanding of the current relevance of neighbourly connections to people’s sense of living well. We will consider the spatially and personally specific and significant characteristics of street level `meeting points’ within and across the two communities.

- To identify whether creative intervention and exchange can stimulate wider neighbourly connections, and contribute to a greater sense of living well in diverse social contexts.

Human Canvas

MobileHome Gallery

The initial research questions to be explored were as follows:

1) How do connections between the people and place where one lives affect and effect a sense of living well?

- How do residents connect at a street level?

- What is understood by ‘neighbourliness’?

- How do these neighbourly connections benefit the lives of individuals, families and the street community as a whole?

- What are the barriers to connections on a residential street?

- How well do specific ‘groups’ feel included in their street?

2) Can collaboration and creative intervention positively impact upon the wellbeing of a street?

- By stimulating new and deeper connections between residents?

- By providing a means for expression that may not otherwise be articulated?

The project had three key stages:

- February-April 2017: Research and development with key stake holders. The team contacted residents though leaflets, which were followed with house visits to provide additional information, and invitation to participate through a) completing questions on a postcard about well-being and street life b) collaborating in the photographic Mobilehome Gallery project c) a 30 minute qualitative interview at a later date (up to six in each street, selected on the basis of indicative case studies) d) organising their Street Party. Cameras were allocated to streets and circulated between neighbours. Mobilehome and Human Canvas were introduced to streets by artist.

- May-June 2017: There cameras were collected. The team organised street meetings to plan street parties and present slide shows of unedited photos. The street parties were held and Mobilehome Galleries unveiled. Responses were collected through conversations, photographs, chalking, and the Human Canvas. After which there were follow-up qualitative interviews.

- July 2017: There was a final analysis of material and a report written. And street postcards were produced for the residents.

Who are the team and what do they bring?

- Patricia Kennett (Policy Studies, University of Bristol) is a researcher of ethnographic research methods and social and urban policy. Her specialities include comparative and international social and public policy; cities, sustainable development and social change; governance and the global political economy.

- Antonia Layard (Law, University of Bristol) is a researcher of law and geography where she explores how law, legality and maps construct space, place and ‘the local’.

- Gaby Solly (Streets Alive) is Director of ‘Streets Alive’ with expertise and experience of engaging with residents, researching and working creatively at a street level in a variety of neighbourhoods. Streets Alive is a national organisation that promotes the use of residential streets as social spaces: Places where neighbours can build themselves stronger, safer, more sustainable and inclusive communities.

- Scott Farlow is a socially-engaged multimedia artist. His work explores the ordinariness, distinctiveness & everydayness of here, there & everywhere. Scott has extensive expertise in activating both public and private spaces and the imagination through unexpected encounters, creative exchange & collective endeavour. His activity and social dialogues result in both temporary and permanent artworks as portraits of time, place and personality.

- Simon Hankins (Southville Community Development Association) is an activist who supports community projects that improve the lives of people living in Greater Bedminster, particularly those that reduce loneliness and isolation for older residents.

- Sado Jirde (Black South West Network) as director of BSWN she rebuilt the organisation’s profile and repositioned its role from an infrastructure body to a racial justice incubator, where alternative solutions to systemic racial and socio-economic inequalities issues are developed in collaboration with the Black and Minoritised communities across the City of Bristol and the South West region.

What were the results?

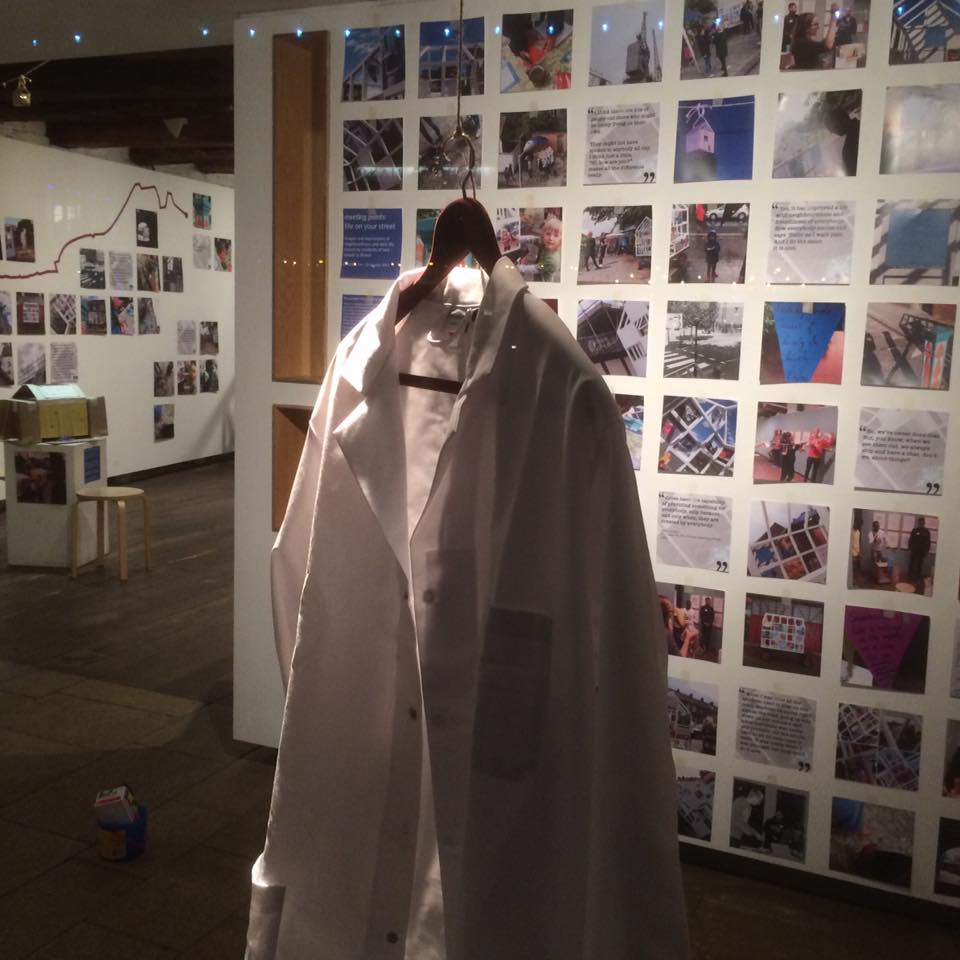

Outputs consisted of mobile galleries of residents’ photos, which were unveiled on each street at their own street party, which were then walked across the city to connect the two streets and, was finally, brought to the Brigstow showcase.

Photo from the project “Jayne on a Stepladder”.

Photo from the project “Kids Playing in Closed Street”.

Photos from the project were also put on display at The Architecture Centre.

Scott Farlow documented the project on his website.