Deep in the rural heartlands of central Colombia, in territories wracked with violent conflict for decades, women have kept fields flourishing and communities alive. Campesino (peasant) existence in the Middle Magdalena hinges on a history of struggle (Ferro and Tobón, 2012; Molano, 2009). These natural resource rich lands have been at the centre of territorial battles between various armed actors for generations. Conflict has consisted of territorial control over oil reserves, gold mines and coca crops, at the expense of tropical rainforests teeming with jaguars, Colombian red howlers and South American tapirs. In this delicate and volatile landscape, campesinos have settled and sustained their communities on the banks of the river Magdalena, the country’s fluvial artery. Many are victims of displacement from other regions. Nevertheless, they continue to live under the constant threat of land dispossession amongst many other uncertainties.

The high levels of violence, disappearances, displacement and historic campesino resistance in the Middle Magdalena has been heavily researched; however, the role of women campesinos is comparatively absent. The need to explore and recognise the particular importance of women in sustaining these communities, lands and families inspired the project: ‘Peasant and Popular Feminism: Co-constructing Peace and Sustainability’. We were also influenced by the Latin American campesino feminist movement in La Vía Campesina, ideas from which informed the projects concept of feminism and women’s agency. In turn we aimed to contribute a more grounded understanding of peasant and popular feminism amidst conflict in the Middle Magdalena.

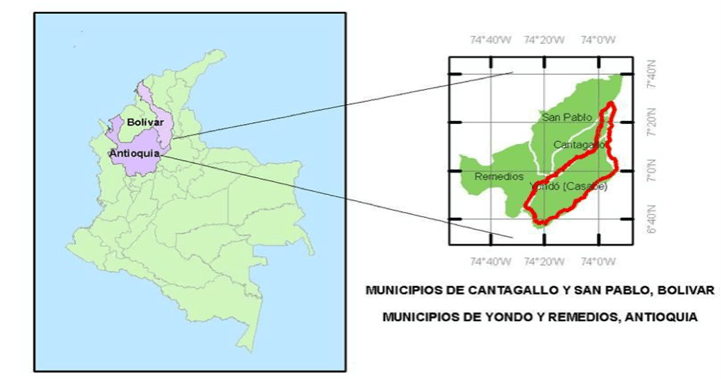

Supported by the Brigstow Institute, our team conducted research with the women of the Zona de Reserva Campesina (Peasant Reserve Zone)- Valle del Río Cimitarra (ZRC-VRC).[1] Framed by an ethos of feminist activist-research, the project was co-constructed with leading women activists from the Asociación Campesina Valle del Río Cimitarra (ACVC)- the main peasant organisation in the ZRC-VRC. The aims were to explore the role of these activists in various socio-political organisations, within community projects and on their farms. We established that it was necessary to highlight the work many women are doing collectively and individually to support the construction of feminist pathways to peace. The project interweaves women’s ideas, histories and practices from the ZRC-VRC, which together express local peasant and popular feminisms. These feminisms are rooted in peace, in female economic and social autonomy, in community, in family, in environmental well-being, in the guardianship of traditional cultivation and medicinal knowledge, and against domestic violence.

Feminist Pathways to Peace

Women’s knowledge, their strength and importance has been undervalued the world over. This is no less true in the Middle Magdalena region, where traditional gender roles that confine women to the domestic sphere and caring duties are prevalent. Only too frequently, women are considered and consider themselves first and foremost as mothers and homemakers. Consequently, many interview participants responded to questions about their roles on farms and communities as “firstly, I am a housewife, I look after the family and the home”.

As well as mothers, carers and housewives, however, numerous women also occupy leadership roles in their communities as presidents of local community councils, participants in women’s committees, catalysts of informal economies, and guardians of traditional or organic agricultural knowledge. One of the local leaders reflected: “women are always the ones who are pushing forwards, the ones that are there to accompany [processes], and to lead”. Many of these women arrived in the Middle Magdalena as victims of displacement due to the conflict. Nevertheless, they have built strong connections not only between themselves but also to their land and territory. They are pioneering pathways to alternative development through their farms but also collectively through women’s committees.

Between February and July 2023, we visited women’s committees in two municipalities in the ZRC-VRC (San Pablo and Cantagallo). These municipalities are home to the ZRC-VRC’s most active committees, which work on ward level development to organise and connect women to specific economic projects. Women’s committees begun in 2005 in the municipality of San Pablo, Bolivar, but they had more cultural objectives, as they were spaces for sewing and dancing. There are currently 25 women’s committees in the ZRC-VRC, which have now become hubs in which women come up with project ideas, apply for funding and then administer economic projects together.

The rural ward of La Victoria in Cantagallo, Bolivar, has the most emblematic women’s committee, which began a local convenience shop in 2007. This has been a resounding success and important source of income for the women in this zone, which heavily relies on earnings from coca and mining. A leading campesina from la Victoria’s women’s committee recounted how they fought for recognition with their male partners and within their communities to lead this project, “but ever since we set up our women’s committee and the shop, we changed our lives a little”. This has been an example not only within the community, as a younger generation of women in La Victoria are preparing to open another shop, but also in neighbouring wards, as the women’s committee in La Palua has started an agro-input store.

Another key collective project led by various women’s committees is ‘hen laying’. This consists of collectively breeding hens and selling their eggs to the wider community. The project has been effective in several wards including La Palua, Cantagallo and La Union, in the municipality of San Pablo, Bolivar. The ‘hen laying’ project draws from a long tradition of small-scale poultry farming led by women (Angarita and Zapata, 2020), in which they rear a diversity of small animals in their patios usually for familial subsistence. In some cases, the collective hen/egg projects have inspired others to become independent sellers within a local informal poultry economy. This project is just one example of women working towards the food sovereignty of their communities, as many also maintain their own vegetable gardens, save seeds from previous harvests and grow medicinal plants. In this sense, they are repositories for a wealth of traditional knowledge and practice.

“I feel that here, we have accumulated experiences and traditional knowledge, because there are many people who have worked on community projects, and…have lived here all their lives working for the common good” (Female leader in the ZRC-VRC)

Upon first meeting us, several participants were shy and reserved, but behind their farm gates they have constructed neighbourly networks, woman to woman, where they sell eggs and meat among other products. One such campesina told us that during the pandemic, when trading outside the community was tough and physically restricted, she made and sold biscuits that were wildly popular. She attended meetings, such as those for the women’s committee, and used these spaces and places of connection to sell her biscuits. The committees and other workshops organised by the ACVC have been crucial sites of formation for these women. One leader recounted that the ACVC “has really taken women into account, especially considering the president is Doña Irene- a woman from the countryside who has really worked hard to support this work”. On the ground this has resulted in participants repeatedly noting that before “a woman had to stay in the house, now she doesn’t have to… now she says that I won’t stay there, I am going to do this”.

Women Cultivate for Life and Peace

Communities in the Middle Magdalena are accustomed to existing in the shadows, mainly due to the conflict and illicit economies, as living unobserved is a survival mechanism. The secrecy that is related to this context has further reinforced the erasure and silence around women’s agency and labour in the Middle Magdalena. Traditionally women’s labour is hidden behind the double burden, whereby domestic and care work remains unremunerated; however, in conflict settings their lives and contributions are even more obscured. Arguably, they have particularly important roles in conflict settings, as historically they are the ‘ones left behind’ if husbands are captured, arrested or killed. This was further reinforced by those involved in the coca economy, in which women are active participants in sowing and harvesting coca but often avoid selling coca-paste to intermediaries if they can. Some noted that if their male partners were captured, at least they would be ‘left’ to look after their family, home and farm. A leading feminist activist from the area highlighted that ‘women campesinas, have played an important role in protection and in caring… women have been a constant here, looking after each detail in sowing the crops…in conservation’. Evidently, women are crucial to the survival of socio-ecological communities in these precarious spaces of conflict.

This project aims to support women activists from the ACVC to highlight their strength, knowledge and leadership, breaking the overall silence surrounding them and their work. Women are the centre of their homes, undertaking arduous caring and domestic labour, but also in their communities through spaces such as women’s committees. Although few identify with concepts such as feminism, when tying these collective and individual stories together, many are effectively building feminist pathways to peace. This consists of women taking leadership of projects and recognising themselves as knowledge-bearers, therefore empowering themselves collectively but also in families and homes. In so doing, they are constructing alternatives to coca, building ties amongst each other to combat the mistrust and disconnection arising from conflict, as well as growing food that nourishes their immediate families and others. As the women involved in co-designing the mural painted in Bajo Cañabraval, San Pablo, noted: ‘women cultivate for life and peace’.

Muralist: Álvaro Saúl Pérez Peña

Co-designed mural from the project, depicting the rural economies that women participate in and lead: ‘Women cultivate for life and peace’, painted in the ward of Bajo Cañabraval, San Pablo.

Find out more about the project on their project page “Peasant and Popular Feminism: Co-constructing sustainability and peace in Colombia“, this is also includes a podcast created by the research team in Spanish.

References

- Angarita, A; Zapata, F. (2020). Producción Agroecológica de Gallinas Criollas. Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios. Bogota: Colombia.

- Asociación Campesina Valle del Río Cimitarra; Corporación Desarrollo y Paz del Magdalena Medio; Instituto Colombiano de Desarrollo Rural. (2012). Plan De Desarrollo Sostenible (2012-2022). Barrancabermeja: Colombia.

- Chohan, J. K. (2020). Incorporating and Contesting the Corporate Food Regime in Colombia: Agri-food Dynamics in Two Zonas de Reserva Campesina (Peasant Reserve Zones) (Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London).

- Ferro, J; Tobón, G. (2012). Zonas de Reserva Campesina y la Naciente Autonomía Territorial. Autonomías Territoriales: Experiencias y Desafíos. Observatoria de Territorios Étnicos. Bogota: Colombia.

- Molano, A. (2009). En Medio del Magdalena Medio. Bogota: Colombia.

[1] The ZRC-VRC is essential to campesino history of resistance in the Middle Magdalena and therefore was crucial to our research. The ZRC model is a legal framework that prevents land concentration, promotes preferential access to institutional funding and provides pathways to alternative, sustainable, campesino-led development (Acevedo and Chohan, 2019; Chohan, 2020). This grassroots development initiative was the culmination of decades of land-based struggle, not only in the Middle Magdalena but also in other similar coca growing regions in the South of Colombia. The importance of the model to agrarian reform and the conundrum of sustainable peace-building was further recognised in the 2012 peace agreement between the Colombian state and the demobilised, left-wing, guerrilla group FARC-EP, which identified the model as key to agrarian reform.