Learning from each other – lessons from the “Living financial resilience” community research and design project

By Anne Angsten Clark, from Living Financial Resilience

In 2022, we partnered with Boost Community, a collective of advice agencies (debt, benefits, housing and employment advice) at the Wellspring Settlement, and community researchers to explore lived experience of financial resilience and together develop ideas how to better support it.

We were a diverse group of collaborators: for many of us English was not our first language and we had different levels of formal education, experience with the community and familiarity with the issues we were exploring. For all of us, this was the first time doing collaborative research of this kind. This raised important questions, mostly how to make sure that the language and processes we would use in this project would feel intuitive and accessible to all, yet adequately reflect the complexity of the topic we were researching.

In this blog post, I want to share a few things I learned as one of the academics in the process:

Language

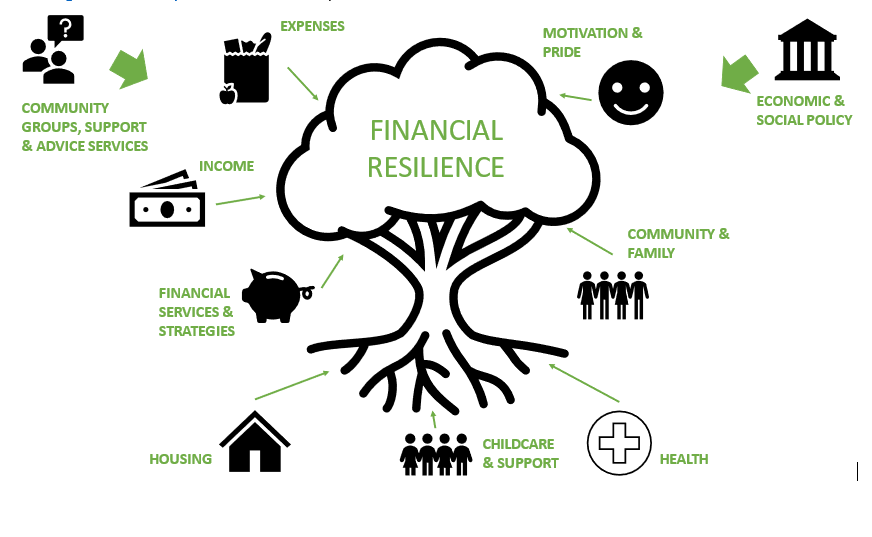

As we were preparing for the first workshop with community researchers, one of the questions we reflected on was language and how to use terms that were intuitive rather than needed lengthy explanation. One of these words was “resilience”. Given that it was at the core of our project, we couldn’t just leave it out, but even in academia, the term often lacks a clear definition. In the end, we came up with a few analogies – a tree, a growing child, a business during COVID – to explore what resilience can look like and develop a joint understanding. The tree proved the easiest analogy: trees need to be strong and flexible at the same time to weather storms, they need strong roots to ground them and sun, water and fresh air to keep thriving. In our regular co-analysis sessions where community researchers shared their impressions and learnings from interviews, rather than referring to resilience, we started asking ourselves: What is helping this person grow roots? How are they trying to expand their branches? What are they missing to thrive? In the end, our final framework of resilience turned out to be… a tree! (See here for a summary of our findings and the tree: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/policybristol/policy-briefings/community-centred-services/)

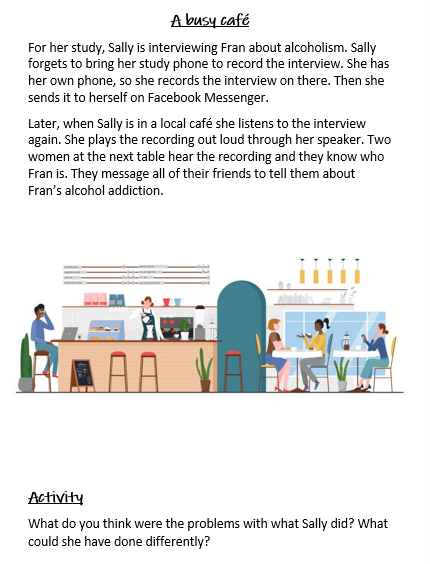

Another area was ethics. As we were dealing with participants in potentially vulnerable situations and we wanted to ensure that community researchers could independently conduct interviews, it was important that everyone had a comprehensive understanding of the ethical and safeguarding considerations. But terms like “informed consent” or “data withdrawal timelines” don’t really roll off the tongue… My colleague Caitlin developed a series of ethics scenarios that brought potential issues to life, for example Sally who forgets her recording device and instead records an interview on her phone to send to herself via Facebook Messenger later and listen to in a busy café. Discussing these scenarios helped crystallize the key ethical and safeguarding principles (which in contrast to the terms we use tend to be quite intuitive) and build a joint understanding we could build on before jumping into the technicalities of the consent form.

Writing less – talking more

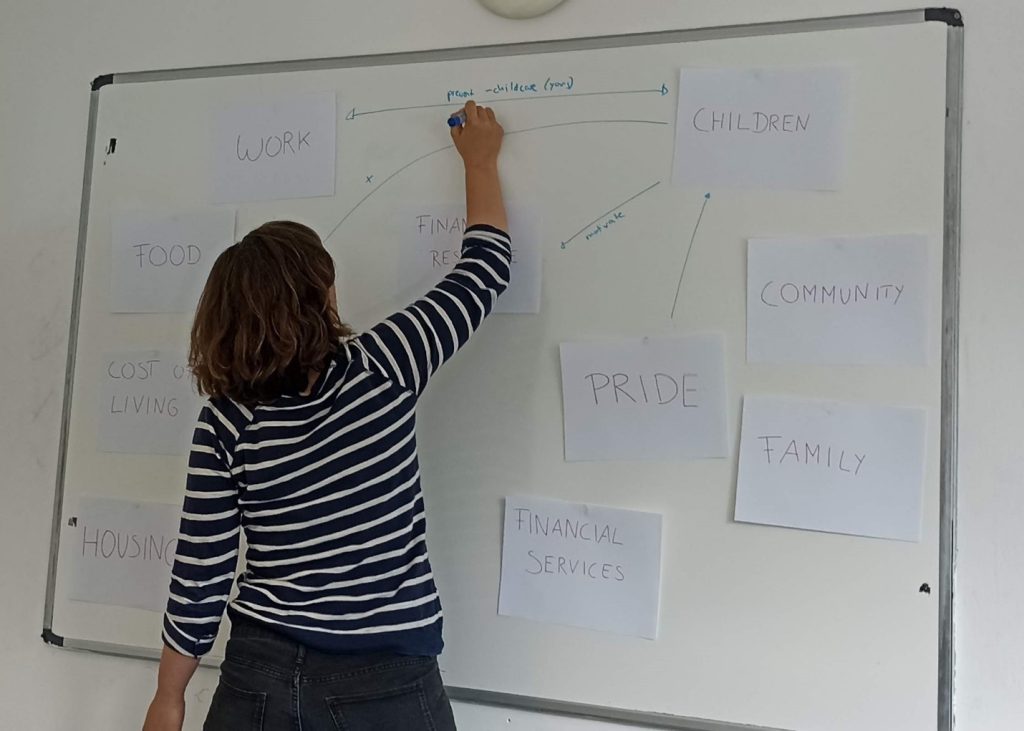

One thing we noticed relatively quickly was that reflecting out loud came a lot easier to us as a group than reading notes or writing up findings. So, after interviews, rather than taking notes, community researchers debriefed together and recorded voice notes summarizing both what they had learned during the interview and what their impressions were. Sharing these voice notes with us in real time also meant we could follow along and keep up during the process rather than just at the end. We met regularly for co-analysis sessions where much of what we did was talk. Community researchers recounted interviews, we shared what we had learned from listening to the debriefs, and together we started developing themes and insights verbally. We would record these on large A4 sheets that often just had one word on them (e.g. housing) and use the wall space to arrange them, trying to show connections or highlight gaps. While we still took notes during these workshops and documented learnings and themes in a more detailed written format later, keeping most of our analysis verbal and tangible on the wall helped all of us reflect together and treat it as work in progress rather than a formal written output that shouldn’t be changed.

Facilitation tools

I teach innovation and design thinking at the Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship and the design thinking process is full of ingenuous facilitation tools and tricks to help you stay creative during the process. However, this project made me reflect on how often these tools are targeted towards a certain kind of designer – someone who has been educated in a way that encourages critical thinking, being quick on their feet, feeling comfortable expressing their opinion – rather than being accessible and inclusive to those new to the process or more hesitant to engage in something so unfamiliar. For this project, I found that simple tools often worked best and brought out creativity in everyone without feeling intimidating. Along with being visual and using all the wall space we had to map out our themes and insights at every workshop, the tool we ended up using most often was a very simple 1-2-4-all technique: everyone first spent a few minutes reflecting on a question on their own (e.g. walking around the room and taking in what we had put together on the wall), then discussed with a partner, then discussed in a group of four and lastly, we all came together as a group (depending on group size, we sometimes skipped the 4 step and went straight to the group from pairs). This tool provided structure and allowed participants to build confidence in their ideas – from having space to think through them on their own to first sharing them with just one person before presenting them to the room. It also meant that those less comfortable speaking in front of everybody could still have their ideas included via their partner or small group discussions. Using this structure helped us crystallize our insights, identify opportunities for change and develop ideas together.

In our last workshop together, we reflected on the process, what we learned and what we might want to do differently in the future (separate blog post on this to come in a few months!). All of us – community researchers, Boost team and academics – highlighted how much we had learned from engaging with each other, building relationships and working as a group. That is definitely true for me personally and I have and will continue to take the lessons above along with many others into other research projects.

This blog was written in reference to Brigstow Institute 2022 Experimental Partnership “Living Financial Resilience: A community research and design project with residents of Lawrence Hill“