Narratives and the Grapevine

Tim Kindberg, from Narratives and the Grapevine

The Narratives and the Grapevine project was an exercise in global literature creation and distribution funded by the University of Bristol’s Brigstow Institute. It brought together Grapevine’s Lily Green and Tim Kindberg with Prof Madhu Krishnan and Dr Edward King of the university. We wanted to explore the potential of Grapevine by working with artists and writers in three very different parts of the world where different languages predominate but where WhatsApp is widely used: Bristol, UK (English), São Paulo, Brazil (Portuguese), and Yaoundé, Cameroon (French, English and Camfranglais).

Grapevine is an experimental tool for connecting artists and audiences outside the mainstream. It supports those working in vision, sound, words or video. Grapevine’s Maker tool enables you to connect artwork to gently interactive, multimedia content which your audience unlocks with WhatsApp or Telegram – and shares with friends, family and beyond. No specialised app is required: just the one they already have in their pockets. All they have to do is take a picture of the book cover, postcard, mural or other form of artwork, and send it to Grapevine. The software recognises the image, and sends the first short episode, with prompts to hear more and share.

The project ran from January to December 2020. On the one hand, this is a much delayed end-of-project report; on the other hand we’ve recently realised, to our delight, that in a sense it is ongoing. More on that later.

The project set out to answer the question:

How can you source and generate content from languages and stories underserved by the wider publishing industry? This project seeks to explore if multimedia distribution can democratise access to literature and develop a digital literacy that effectively supports social inclusion.

We explored Grapevine’s potential with respect to those concerns, firstly through workshops with writers and artists in each location, and secondly by commissioning grapevines from selected participants, also in each location. In the workshops, which took place over a day, we asked about the participants’ existing practices as background information, and gathered their reactions to Grapevine as they used it in simple ways – as consumers, not creators. We then asked them to come up with creative ideas for Grapevine, from which one was chosen in each of Bristol and São Paulo, and two from Yaoundé, reflecting the dual Francophone and Anglophone presence there.

Workshops, commissions and sharing

Due to Covid-19, we largely used virtual means to work with partners and artists in the three locations. We found that this worked well overall. While face-to-face meetings would have been preferable, they wouldn’t have been possible in all cases anyway, given the distances and expense involved.

We worked with the organisations, artists, writers and producers described below, plus audio producer Eloise Stevens, and PhD student Penny Cartwright from the University of Bristol. Penny analysed the workshop recordings and organised the final showcase. This article is partly based on her analysis.

For each location, we now describe a selection of findings from the workshops to illustrate some of the differences between them, followed by the commissions. As always with Grapevine, you can unlock the content by sending a photo of one of the images below or saving/sharing it from this page to either WhatsApp +44 7380 333721 or Telegram @GrapevineMediaBot.

Yaoundé

We partnered with Dzekashu MacViban and Bakwa who recruited participants from across the country, evenly split between the Anglophone and Francophone regions. Georgina Collins ran the Yaoundé workshops and produced the commissions: one in English, the other in French.

In the workshops Grapevine was viewed, at least initially, as having concrete political and educational aims, and more formalised/ institutionalised audiences than was the case in the Bristol and São Paulo groups. Later, however, more literary aims, centring around language use, became apparent. Participants expressed a desire to legitimise vernacular and local language creativity and to develop a visible and established literary space for Cameroonian writers more generally.

Language was identified as a fraught issue by the majority of participants, with one stating that “on a un problème politique des langues” [there is a political language problem]. Language engagement was clearly associated with social cohesion. Grapevine was posed as a way of overcoming linguistic-cultural barriers – “because of art we came together” – and promoting “un mélange des langues” [mixture of languages]. WhatsApp is very popular in Cameroon, perhaps the most popular platform after Facebook.

Street Smart Stories

Street Smart Stories

Writers Nkweti Anjie, Nnane Ntube, Bendie Sidney, Tita Hans and Edmund Elume, and visual artist Dante Besong created this commission. Street smart stories portrays, in the form of creative non-fiction, the lives of people on the streets, across four episodes of audio with signature images. From Moussa, the beggar on the street whose meals depend on a kind stranger, to the shoe mender, Mrs kok kok, who must work in a man’s world to survive, and Frank the truck pusher. Life is hard but they keep pushing.

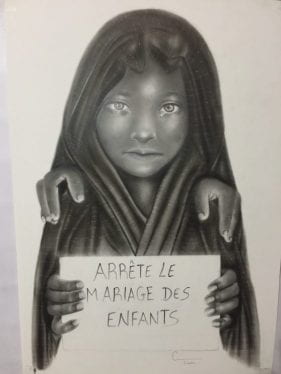

Arrête le Mariage des Enfants

Arrête le Mariage des Enfants

Writers Raoul Djimel, Géraldin Mpesse, Gils Da Douanla, Edouard Bengono, David Djomeni, Annie Claire Ngomo, and visual artist Cédric Chop created this commission on the subject of child marriage. They recorded four poems, each with its own Grapevine episode.

São Paulo

We worked with artist/producer Rafael Coutinho who recruited participants from around Brazil, ran the workshops and produced the commission.

WhatsApp plays a major role in Brazilian society – as it does in the UK and Cameroon, but with a somewhat different flavour. As Coutinho says, “Whatsapp is way more spread out and popular then all the other platforms of social media in Brazil, including Facebook. Brazilians embraced WhatsApp, it’s an important part of people’s lives, relationships, how we inform ourselves, we express discontentment and humour. The dissemination of memes through Whatsapp in Brazil is quite unique, I think mostly because of our humour.”

The São Paulo workshop focussed on comic books. “Compared to literature or drama, the comics community is quite small in terms of cultural presence,” Coutinho says. “But it grows when presented to a wider audience, in events such as CCXP, where the geek audience expands and connects to other mediums such as TV series and such. When closer to educational agendas and public funding, it also resonates more in the Brazilian spectrum […] It is my feeling that if disconnected from other interests of the public, it becomes very isolated and ‘bubbly’. WhatsApp is one of those bridges.”

There was an interesting difference from the Bristol workshop, where the use of physical printed artefacts such as postcards, posters and flyers attracted interest as a way of expanding the reach of an otherwise live event. From his Brazilian perspective, Coutinho observed that sending images from screens would scale better: “connection would be determined by the amount of flyers sent (and since this is a test of a theses, we’re going to do only with one comic book store in São Paulo), but we believe that if transformed into a digital campaign, using the Grapevine artwork in websites and WhatsApp, we could expand way more the number of people listening to it.”

Billy Soco

Billy Soco

Rafael Coutinho (São Paulo), Diego Gerlach (São Leopoldo), Gabriel Góes (Brasília) and Lila Cruz (São Paulo) developed and produced this commission, based around a satirical superhero comic character created by Góes. Listeners can hear five episodes in Portuguese which narrate one of Billy Soco’s adventures and are designed to expand the world of the print comic. There is also a critical piece by Ciro Marcondes in which the journalist places the comic in its artistic and political contexts. This grapevine was designed to be placed within a comic shop in São Paulo called Loja Monstra.

Bristol

Lily Green recruited the participants for the Bristol workshop, and it was run by Heather Marks (producer) with assistance from Tim Kindberg. Lily also produced the commission.

The Bristol participants practised a broad range of art forms, including video, live spoken word and music performances as well as writing and the visual arts. There was a greater interest shown in the use of printed artefacts than in the other two locations. For instance, one participant observed that prints tags with grapevined content could be used as a way of physically moving people into venues that they don’t usually approach (e.g. Arnolfini, a local Arts venue); another was interested in people taking content away from his live performances, in the form of grapevined flyers.

WhatsApp was regarded as a very distinct medium in terms of audience compared to Instagram, Twitter and other major platforms. A bonus was that it was seen to remove a pre-requisite of having to be ‘cultured’: of one needing to know what is currently trending. On the other hand, it was seen as one medium among several that the artists would use to reach their audiences; important conversations (e.g. contemporary masculinity) would take place across several social/physical media – allowing people to engage wherever they are most comfortable.

What in the Werburghs

What in the Werburghs

Ella Scotland-Waters created this commission, a visual and audio portrait of the St. Werburghs neighbourhood of Bristol, which was tagged to a poster. In the first two episodes, we heard from local residents about the place; in the third was a sequence of images of local places.

Sharing Day

On December 2nd 2020, after all the commissions had been produced, we held a “sharing day”. Each city was represented by the artists and producers, who had an allotted 30 minutes per commission to speak about their work and hear feedback from everyone else.

We held the sessions via a WhatsApp group – appropriately enough, given that that is the platform by which all of the commissions were experienced (Telegram was not used). We sent selfies so that everyone could see one another and where we were. Of course, not everyone spoke the same language but enough of us use English and French to be able to present all the projects to most participants – even if none of us could perfectly understand all the commissions, which were in English, French and Portuguese. This diversity was an interesting fact about the project as a whole: we were people in three countries with differing languages and cultures, all intersecting only partly with one another when it came to our practices and our interests, but all sharing a single platform (Grapevine/WhatsApp), and a commitment to the written and spoken word and/or to the visual arts.

There was a lively conversation and considerable appreciation of the works produced, despite the linguistic barriers. As one participant observed of a particular piece, “Even though I can’t understand the language, I love the calls, the voices, the car horns and the music. Very immersive.”

Asked to give feedback about Grapevine overall, while some aspects of the prototype have rough edges, the artists appreciated its overall simplicity. This includes that one both unlocks the content and shares the content by sending an image – either to Grapevine, or to a friend together with a message along the lines of “let’s see what we have on this pic.” As one participant put it:

“we have seen Grapevine at the beginning as a way to share and communicate. A way to spread.”

Afterwards

This project has been a fantastic experience for all of us in multinational, multicultural research – especially since, in conducting it, we transcended the Covid-19 lockdowns that have inhibited us locally. In principle, a global messaging app with two billion users is a good basis for inclusive, global literature dissemination. But we are interested in how to bring this about in practice. For all the questions that remain, we are greatly encouraged by the inputs from the three cities we worked with.

Even though we have been completely “hands-off” since December, Streetsmart Stories and, to a lesser extent, Arrête le Mariage des Enfants, are still circulating in Cameroon and beyond. We have recorded them in Canada, Germany, Denmark, the UK, Ghana and Nigeria. Users in Cameroon occasionally send us feedback via the Grapevine number, without us asking for it. This was received recently, about Streetsmart Stories: “The story is beautiful and I like the sound and feel it comes with it 👌👌”.

Grapevine is now about as popular in Cameroon and India, where another project is using it, as it is in the UK. Multimedia distribution using Grapevine has democratised access to literature, at least to this degree.