All mankind is of one author, and is one volume

Tim Senior, Tom Metcalfe and Marianne Ailes, Medievals and Moderns in conversation

John Donne’s evocation of human connectedness across space and time is a fitting sentiment for our Brigstow-funded project “Medievals and Moderns in conversation”. Here, we’re asking how the long-history of our rural medieval churches might help us imagine new roles today for church buildings in their communities. As part of this work we’re developing an interactive audio tool to help us work closer with our community partners at Brockley in North Somerset. To date, we have conducted a number of face-to-face interviews with residents concerning rural life; our ambition is now to open-up this process further, bringing other perspectives into our conversations and creating new routes for participation in the process. Thinking beyond our earlier interview approach (see insight post here), we want to support a more open-ended, reflexive, and collaborative engagement with people’s stories at Brockley. In the first stage of this project, we’re asking how new technologies and a deeper engagement with the long-history of Brockley might help us achieve this.

Taking the Long View

In Medievals and Moderns our central interest lies in how the long-view of communities – back to the medieval period – might change the way we think about the future of our under-used historic churches. St Nicholas’ Brockley is one such church. Since its release from the parish into the care of the Churches Conservation Trust, how St Nicholas’ might now best support its community has become a pressing question.

Why are we turning back to the medieval period for new insight on a modern problem such as this? There is, perhaps, a risk that we inherit today too-narrow a view of our historic churches either as spaces ‘isolated’ for Christian worship or as works of ‘religious art’ to be preserved at all costs. Although there is nothing intrinsically wrong with either of these positions, they can act to limit our view of the rich relationships that have sustained churches and their communities (today as in the past), or might make claim to historical continuity (“this is how it is, and this is why”) that misrepresents the past in some way.

Looking back to the medieval period at St Nicholas’, we encounter a very different relationship between faith and community to the one we see today, the subject of a future insight post. Suffice to say, what the long-view can open up is new ideas for creative and meaningful relationships between a church and its wider community. We want to ask if the perceived gap between church sites as “sacred heritage to be preserved” and “community hub responsive to current needs” might be a largely conceptual one – something that can be tackled by taking the long-view. In this insight post, we’ll focus on the new interactive device we’re developing to help stimulate exactly these conversations at Brockley.

A Role for New Technologies

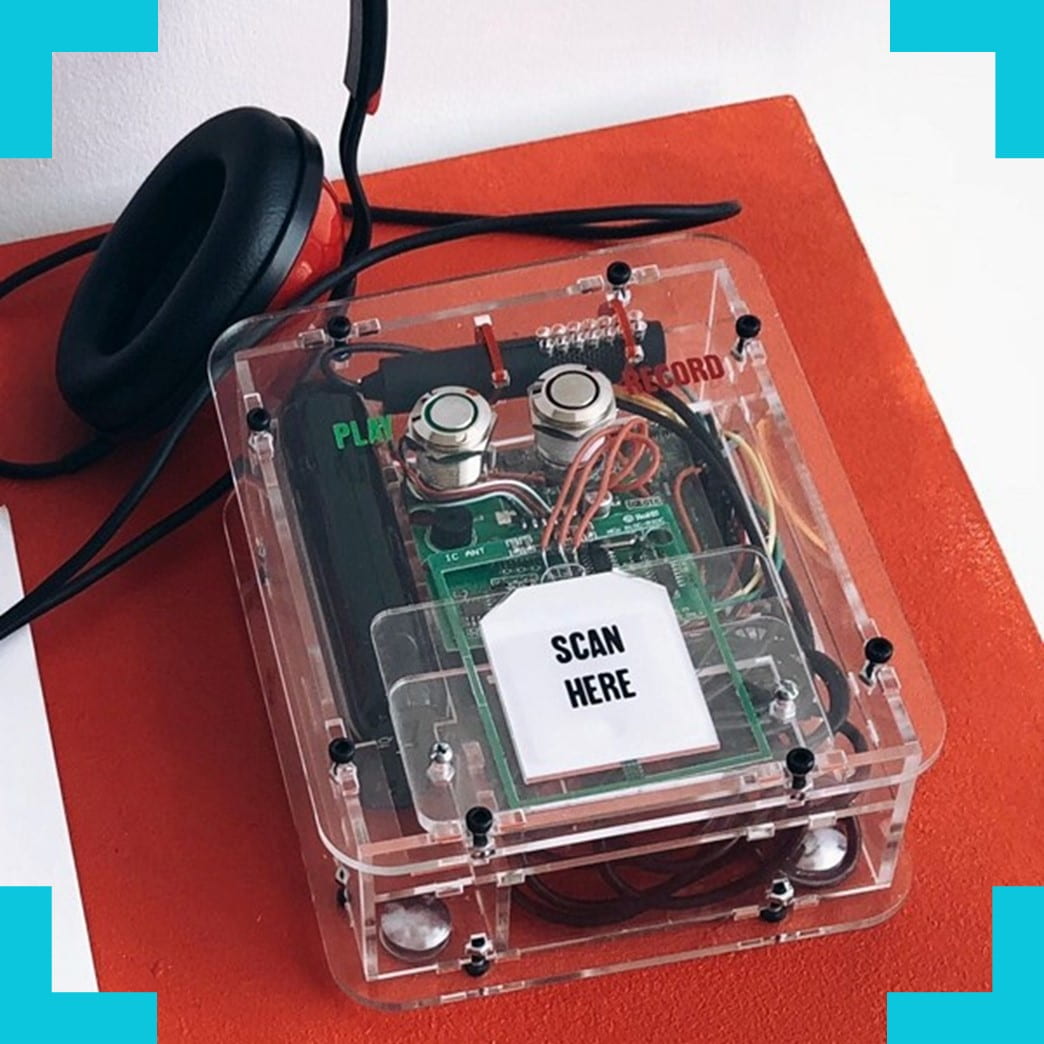

The building block of our interactive device is the Jigsaudio system developed by Alexander Wilson at Newcastle University’s Open Lab research group (http://jigsaudio.com/). At the base station (Figure 1), Jigsaudio technology allows you to record an audio file and give it a unique identification tag. This unique tag can be associated with any other physical object, such that when the object is placed against the base station, that specific audio file associated with it can be played back on speakers. In this project exploring rural life today and the future of St Nicholas’, the Jigsaudio system can help us record people’s stories, perspectives, ideas, and questions as part of an ongoing conversation – this might be through an organised workshop or opened up to more spontaneous individual contributions over a period of time.

We see this as an example of how ‘slow technology’ can be used to give people more time in crafting (or reconsidering) a response to difficult questions about place and place-change. It’s an approach that can release time to work together, open up different conversational moods (both formal and informal), and introduce conditions that encourage people to contribute in a thoughtful and respectful way. As slow technology, the physical element of Jigsaudio devices is also very important. Highly portable, it can be setup just about anywhere, meaning that its design and installation can be tied with the special characteristics each space has to offer. Finally, the device’s tagged objects, each with a unique associated audio file, can be assembled together to form a physical community storybook at the site in question.

Connecting Conversations with Objects and Places

In the conversations we want to hold at St Nicholas’, there are three different pairings between place (where a device is situated) and theme we want to explore: The first is the font, where we will focus on themes of community identity across generations – past, present, and future; the second location is an 18th-century family box pew, where we’ll focus on the role of St Nicholas’ in constituting and structuring community in different periods; finally, a third device will be kept entirely portable, focusing on people’s personal stories, hopes, and ambitions for life in Brockley. Through the tagged objects described, we will introduce ideas from the long-history of St Nicholas’, a means of shaping these three “sited” conversations.

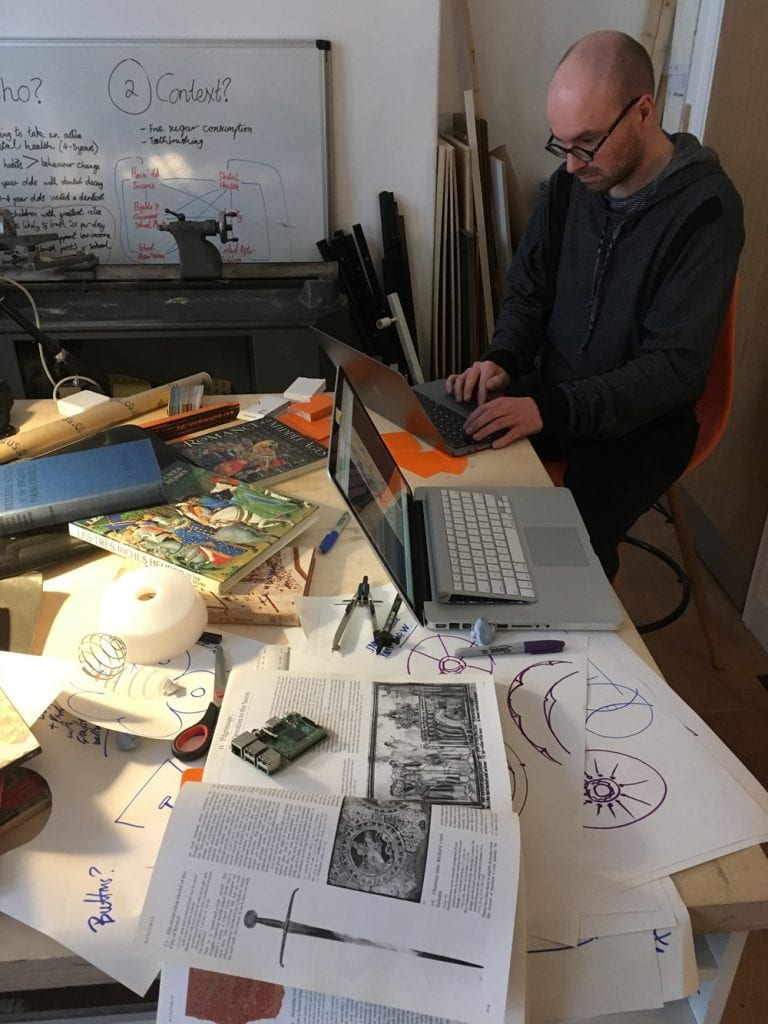

As an open-source device (meaning the software and hardware design are available for anyone to use free of charge), the Jigsaudio system comes in ‘barebones’ form. We are treating this as an opportunity to design a casing for the device that is special to the project and its use in a church setting. Getting the design right is an important step (figure 2). If done well, it can help cement the idea that re-thinking St Nicholas’ future is nothing new – an ongoing process with a long pedigree; if done badly, it risks staging this project as a temporary ‘intervention’ – one that can change nothing.

A Symbolic Starting Point

Our aim is to design a device casing that is firmly the product of our time whilst also one drawing on the heritage of St Nicholas’ and Brockley. A key design position is to avoid coming too close to a ‘religious object’ (something imitative of a liturgical vessel or church furnishing); rather, we want to draw on design motifs that recognise Brockley’s indebtedness to the Christian Faith whilst also acknowledging that St Nicholas’ future lies in its support for the whole community. Our starting point has been the term ciborium, from which both chalice and canopy are derived. Each symbolises divine presence, but in different ways: one – held, contained, and embodied; the other – overhead and all-embracing. The significance of container and covering is a far reaching one in our human story; it both predates and reaches beyond Christianity alone.

With an etymology that describes an open seed pod, the chalice has come to occupy a central position amongst sacred vessels, the cup in which the wine and water of the Eucharistic Sacrifice is contained. Other altar vessels, such as the Ciborium or Patens also echo the significance of a hand-held object that signals divine presence. In a similar guise, the canopy symbolises the heavens above ‘down here on Earth’. Canopies have come to take on an enormous variety of forms, scales and functions. We see them as overhangs for processions, wall niches, tombs, statues, and font coverings. (Even architectural ribbed vaults were understood as canopies by contemporary chroniclers). Here at Brockley, canopies are found over the pulpit, in its stained glass windows, and even over the chimney pot in the southern transept. Our initial design adapts this joint symbolism further.

A Prototype

The device (Figure 3) takes the form of a cylindrical object, tapered on the underside and with a deep recess into the upper surface, giving it a bowl- and canopy-like quality. Held in the hand, it has the intimacy of a simple bowl – a symbolic centring for personal reflections on community today; suspended over the font, or held-up in position in a pew, it takes on the form of a small canopy – symbolically embracing each of us within community. Recognising our interest in the changing role of St Nicholas’ (from past through present to future), the device casing will be cast in Pewter, a soft and malleable metal alloy commonly used for everyday objects in the Middle Ages and a material that will itself be transformed through use. As with St Nicholas’ itself, this is not the place for design that is ahistorical or resistant to the passage of time.

Over the inner surface of the device, we will depict a model of the medieval universe as imagined by Dante Alighieri at the beginning of the 14th century in the Commedia. A work of poetry – a love poem – the Commedia tackles the pursuit of a good life in the face of lived uncertainty. In the Commedia, to paraphrase Robin Kirkpatrick: Human existence expresses itself through ‘will’ and ‘desire’ – in an appetite, shared with all other forms of life, to live as completely as possible (Dante Alighieri (2007). Paradiso. Translated and edited by R. Kirkpatrick. Penguin Classics, pxiii). That this is a journey fraught with difficulties is beyond doubt, but it is one we must all embrace. Under lockdown, we are reminded that the historic parish church has been witness to the challenges each generation has faced, providing a beacon for renewal in the most difficult of times. It’s time, again, to explore what the next chapter in that journey might be.

A digital rendering of our proposed casing for the Jigsaudio device (see text above for details)

Image credit: Tom Metcalfe, Telephone Avenue

What’s next?

Since the 6th July, the Churches Conservation Trust has begun the process of opening its churches. This means that, soon, we will be able to return to St Nicholas’ with a working prototype of our interactive audio device, a first step to sharing, testing and iterating its design.